The Risk Whisperers

To view this article in digital magazine format, click here.

There is an official story and a real story behind how three managers linked two of investing’s biggest trends in a paper and, instead of getting laughed at, won broad acclaim. Because the notion of applying a risk-factor framework to liability-driven investing (LDI) may seem like the coupling of Kim Kardashian and Kanye West: pretty arbitrary, except for their respective hotness.

The official origin story of “LDI in a Risk-Factor Framework,” as told by Andy Hunt, a BlackRock managing director and one of the three authors, goes like this: “To understand liabilities for risk management purposes, you have to start by knowing what those liabilities are and what risks they’re giving you,” he says. “And fixed income has always been very good at serving up risk factors.” Hunt and his team had been working in the LDI and risk factor spaces for years, he points out. “It’s very natural to try and find a common language between the two sides of the balance sheet for the purpose of holistic risk management.”

And this is what actually happened: “In reality, we were asked to write an article about liability-driven investing as well as one on risk parity. We thought, ‘Why not put them together under this new banner as they fit ever so well together?’” One suspects that the efficiency of one paper versus two also appealed to the authors. So, like any successful turn in evolution, “LDI in a Risk-Factor Framework” was by and large a happy accident. The paper won the 2013 Redington Prize—a biannual award for the best investment research authored by an actuary. It also defined the paradigm behind a decade of LDI innovation: the risk-factor approach.

It all started with one. Ten or so years ago, before the 2006 Pension Protection Act compelled most plan sponsors to LDI or die, “duration” was the watchword in cutting-edge corporate pension risk management. It was a rough, if simple, measure of a liability’s lifespan, according to Callan Associates Vice President Eugene Podkaminer. He and the BlackRock trio—Hunt, risk parity head Phil Hodges, and strategist Dan Ransenberg—all know one another well. If the risk parity and LDI sectors were on a Venn diagram, these four reside in the overlap. It’s a young, research-driven space that seems more collegiate than cutthroat… at least for now.

“Back in the day, we would talk about liability duration as one number—11.5 years, for example,” Podkaminer says. “Pretty quickly, that evolved into key-rate duration,” a technique to measure a liability’s duration at multiple points across the yield curve. Then came the integration of the spread between corporate bond yields and US treasuries. “For the last four or five years, sophisticated asset management shops and consultants have been applying different factors and metrics to ever more granularly define liabilities: convexity, default risk, et cetera. This goes hand in hand with the research done on risk factors in years prior.”

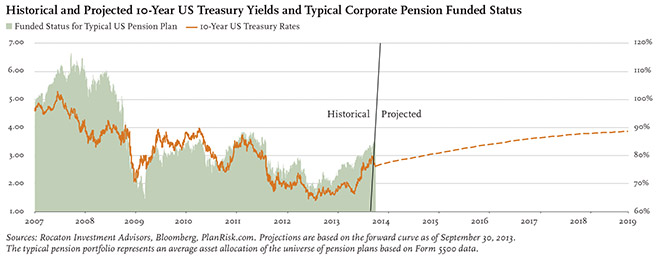

Perhaps four or five asset managers and a handful of investment consultancies operate and innovate at the forefront of factor-based LDI. Each has its own secret sauce. These much-tinkered-with proprietary risk models diverge at the margins, but they share a core of fundamentals. “There is a certain level of consensus on some of the key factors,” says Joe Nankof, a partner at Connecticut-based Rocaton Investment Advisors. “Virtually everyone is looking at either nominal interest-rate risk or its two building blocks: inflation and real interest-rate risk.” Rocaton chooses to break it down. The second agreed-upon factor is spread risk, as both corporate credit yields and treasuries contribute to the not-so-secret funding status methodology used by US regulators. “The third which everyone would agree on is equity risk,” Nankof continues. “Beyond that there’s certainly difference in opinion.”

The BlackRock paper supports Nankof’s take on the industry fundamentals. It considers “simplified versions” of four of the firm’s in-house risk factors: equities growth, credit growth, real interest rates, and inflation. Neither BlackRock nor Rocaton would divulge the total number of factors in their models. However, Nankof’s colleague Matt Maleri, the consultancy’s director of asset allocation, gives reassurance that risk-factor modeling wouldn’t follow the razor blade industry’s approach to innovation: Just add one more. “We know that there is a limit,” Maleri says. “It’s not helpful for anybody to look at 10 or 15 or 20 risk factors.” Plus, he adds, the three core elements—nominal interest rates, spread risk, and equities—account for roughly 80% of a portfolio’s total exposure. “But that doesn’t mean we’re giving up on the other 20%.”

As risk models have become more comprehensive, so too has their utility for corporate defined benefit plans. Ten years ago, enhanced estimates of duration gave plan sponsors better insight into one angle of their liabilities. Now, the top-end risk models only fully deliver when applied to an entire portfolio and the sponsoring organization’s own exposures. But then again, that’s their selling point.

“You can look at your entire portfolio in risk-factor terms or cleave it into halves: liability-hedging assets and return-seeking assets,” Podkaminer says. When introducing the concept of risk factors to his clients, he’s found the best approach is a simple example: “In your liability-hedging portfolio, you probably have an exposure to credit. In your return-seeking assets, you also have credit exposure. But there is no crosstalk, because they can’t connect. At the most basic level, there should be crosstalk with factors from one side of the portfolio to the other.”

Holistic portfolio management is a lovely and intuitive theory, and Podkaminer’s clients typically respond with interest. But communism and global governance sound just fine on paper, too, and implementation brought us the USSR and League of Nations. Unlike those, the practical complications of applying risk factors to LDI seem to be surmountable. But they do exist. For one, developing a sophisticated risk-factor program would—for most corporate funds—mean hiring an external provider. At present, only a large handful of organizations are on the leading edge of the approach, and they’re all asset managers and consultancies. Education presents a barrier, too, as any of these managers, consultants, or savvy CIOs can attest. Risk factors are a whole new language, and resistance to change can come from any level. Holistic portfolio management runs counter to the common approach of substantially outsourcing assets across many specialized managers.

“I do believe there’s a world of specialization that consultants have driven into asset management,” Hunt says. “But these specialties aren’t necessarily engineered by anyone to fit together very well or be monitored holistically on an ongoing basis. Absolutely people tend to focus on their own piece of the puzzle without much care to what else is going on. With these kinds of siloed managers, if specific risks pop up, they go unmanaged.” Whether or not consultants created the problem of ever-narrowing manager mandates, Podkaminer sees his profession as part of the solution. “Implementing and monitoring a risk-factor approach falls pretty cleanly in the consultant mandate,” he says. “It’s our job to be thinking at a high strategic level about the whole portfolio, and it’s imperative that consultants do so.”

Still, funds need not overhaul their operational structure to work in risk factors. It’s up to CIOs—and perhaps their consultants—to align the fund’s various managers towards one portfolio-wide goal. “CIOs can ask LDI managers, ‘Are you incorporating what I’m doing on the other side of my portfolio in what you’re doing?’” Podkaminer suggests. Those on the return-seeking side also benefit from questioning, he says. “For example, ‘Of all of the capabilities that you have in your shop, Mr. Equity Manager, is this the right product or strategy to implement my objective? Is the flavor of the strategy in which I’m invested consistent with meeting my objectives in terms of high-level goals?’ These kinds of questions can show a lot about a manager’s willingness or capability to work in a risk-factor framework.”

So how many corporate CIOs are asking these questions? In Hunt’s experience as US head of LDI for BlackRock, “implementation of risk factors with LDI has physically lagged the theory.” This aligns with the broader institutional uptake of risk-factor investing—or lack thereof. Most forward-thinking CIOs tend to agree that asset classes aren’t all that useful for building and optimizing portfolios. Nevertheless, only a handful of investment offices -allocate primarily by priced risk exposures. Norges Bank Investment Management, marshal of a US$800 billion pool of assets, is one. Indeed, its mandate declares that alpha “shall be achieved in a controlled manner and with limited systematic exposure to priced risk factors in the markets.” The New Zealand Superannuation Fund is another adherent. It’s likely no coincidence that these investment teams have substantial resources and answer chiefly to professional boards, not politicians or members.

But risk-factor investing, like LDI, exists on a gradient. A plan sponsor that begins hedging a portion of its liabilities by extending fixed-income duration pursues a modest degree of LDI. Likewise, a public pension that adds a risk parity allocation detaches a bit from the asset-class model. Almost no one would argue with Hunt that, among corporate pension funds or any other institutional facet, there’s a lot more conversation than action on risk factors. But his reasoning might be more controversial.

“You need to embrace or facilitate leverage if you’re going to do LDI in a risk-factor framework,” Hunt says. “That has been, in our opinion, one of the greatest hurdles. Don’t buy the theory and give up on the practice.” Clearly, one man’s risk-factor framework is another man’s risk parity. Neither Podkaminer nor the Rocaton consultants define leverage as a real-world lynchpin of factor-based LDI. As columnist Angelo Calvello has vented in these pages many times, definitional issues hamstring this topic. It’s no wonder, then, that risk factors have given rise to so much discussion: Conversations may be going in circles as everyone tries to figure out what the hell they’re talking about, exactly.

From another perspective, LDI itself is an act of basic risk-factor investing: The target is a certain level of interest-rate exposure, while the asset class—say, 10-year treasury bills—is just the vehicle to get there. In other words, LDI compels an investor to be factor-oriented and asset-class agnostic—a mindset some define as risk-factor investing.

Unlike any other breed of asset owner (except perhaps insurance CIOs), corporate plan sponsors have a tangible motivation to embrace risk factors. Regulators have pushed them into it. That shove has been enough to overcome some barriers to implementation that still block other types of institutional funds. Take, for example, board education. Experts or not, trustees will get up to speed on nominal interest-rate hedging if it promises to tame a funded status that’s gone wild—and thus lower the CEO’s blood pressure during earnings season. Corporate asset owners, managers, and consultants have been singled out in the industry and incentivized to think factors. LDI has become the norm; most thoughtful plan sponsors will by now conceive of at least one portfolio target as a risk exposure, and of asset classes as the tools to reach it. And if not, it won’t be for lack of understanding. While the impact of interest rates on their funded statuses may no longer surprise corporate CIOs, a few probing questions to their managers and consultants might. A plan that appears no more engaged in its risk profile than hedging nominal interest rates may have a high-level puppet master overseeing half a dozen secret factors. Or it might not.

Before BlackRock put names to the converging trends, they had spent years in good company building out the middle of the LDI/risk-factor Venn diagram. The extent to which that research trickles up depends on the CIOs. Every risk guru interviewed here knows its bad business to bore or confuse clients with third- and fourth-order discussions of convexity. While they’re loath to reveal their bespoke models, each is keen to prove how busy they’ve been below the surface. For these select asset management nerds, LDI and risk factors have been a fated pair all along.

“Risk management is near and dear to corporate pension plan management, and it’s made more so because of all the regulation that has encouraged LDI,” Podkaminer says. “Risk-factor frameworks are just the next step. It’s not revolutionary—it is an evolutionary step.”