How Did Balanced Funds Weather the Crisis?

“If it isn’t broken, why should we try to fix it?” queries the chair of trustees of the Hypothetical Pension Plan.

The vice chair pipes up: “Since Lehman Brothers imploded, it’s been a rough ride for everyone, but we’ve come through with a 50% return in seven years. I’m happy with that. If we can achieve that in those markets, what are you worried about?”

It’s your first meeting as CIO with the trustee board. Halfway through, you are feeling deflated. You had a radical plan to overhaul an old-fashioned 60/40 portfolio and drag it into the 21st century. You’ve got piles of notes on infrastructure investment, private equity, and risk parity. But all your trustees want to know is, why change at all?

As a publication, CIO covers new and increasingly complex approaches to portfolio allocation and construction. We have reported on innovative approaches to in-house management of assets, partnerships with hedge funds, and even taking direct stakes in companies—all of which have been employed by asset owners around the world.

But we wanted to know: Has it all really been worth it? If you had stood still through the turmoil of the post-Lehman Brothers period, would you actually have been any worse off?

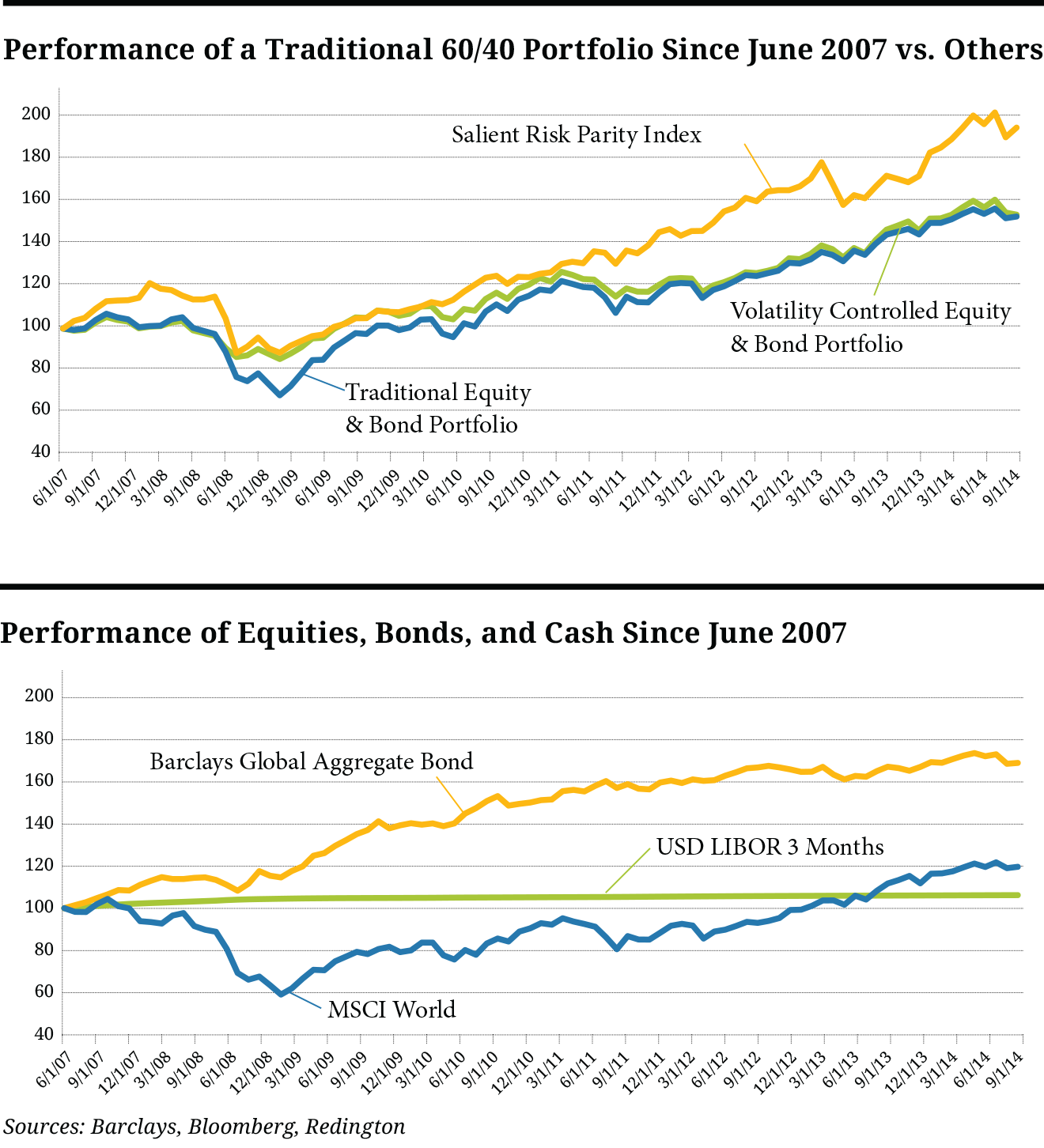

Dan Mikulskis, co-head of asset and liability management and investment strategy at Redington, agreed to crunch some numbers to ascertain the behaviour of a “traditional” portfolio split (60% equities, 40% bonds) between July 2007 and October 2014. This period takes into account the onset of the credit crunch, the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the bottom of the equity market in early 2009, Greece’s sovereign default leading to the first iteration of the Eurozone debt crisis in 2011, and the end of quantitative easing.

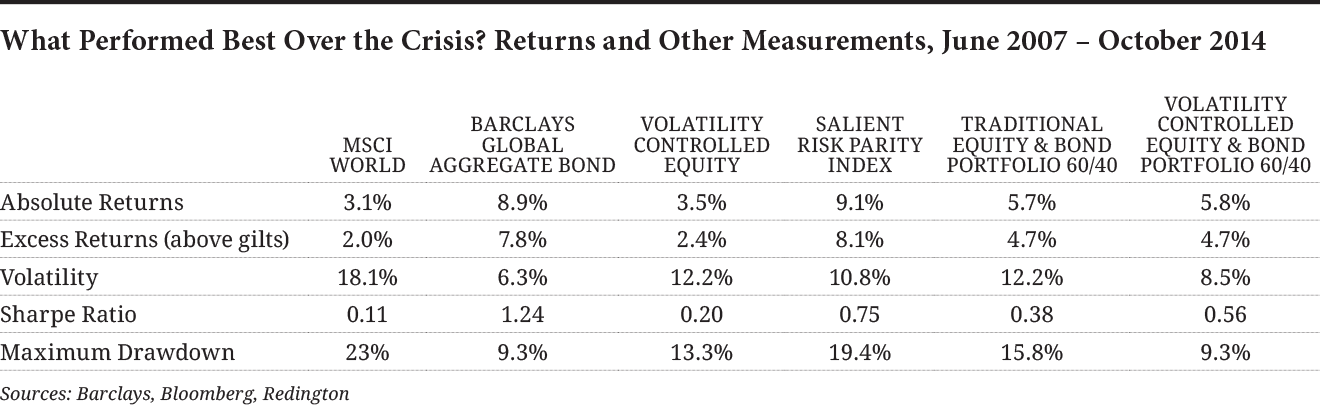

At first glance, the trustees of Hypothetical Pension Plan have a point. In a little more than seven years, a 60/40 portfolio is up roughly 50% by Redington’s calculations, double the return from the MSCI World index over the same period. Bonds, as measured by the Barclays Global Aggregate Bond index, fared even better, gaining 86.6%.

Unfortunately for the trustees, Mikulskis was not that impressed with the results. “We’ve seen a massive fixed-income rally and a strong rally in equities, so I’m not surprised to see that return—but it is modest overall,” he says.

For the funds that stuck with the old model, that 50% return only looks good in isolation. Mikulskis also ran performance for a 60/40 portfolio split with the equity portion invested in a volatility-controlled index, which reduces exposure when volatility increases. This portfolio posted an almost identical return (50.9%), but with significantly lower volatility and drawdown.

“There was a period of high volatility in 2008, so the index would have reduced exposure before that,” Mikulskis explains. It was the same journey, but taking a smoother path.

The Sharpe ratio is higher for the volatility-controlled portfolio, indicating more attractive risk-adjusted returns, and it is this measure that consultants and analysts are most interested in (more on that later).

Ralph Frank, CEO at independent consultancy Charlton Frank, admits that a 50% gain is “in isolation a reasonably attractive return,” but doubts that many pension funds would have gone through the entire crisis period without asking serious questions of the 60/40 model.

Fairly early on, he argues, trustees and pension

fund managers “would have been pretty concerned” following falls of roughly 30%

or, in some cases, much more.

Drilling down further into the construction of a “traditional” 60/40 portfolio, Frank warns of the lack of diversification provided by the Barclays Global Aggregate Bond index, which Redington chose to represent the fixed-income returns in its model. “Your bond exposure is not particularly diversified,” he says. “It’s made up of government and corporate bonds, and so [with the equity portion] you’ve got quite a lot of exposure to the corporate sector. Particularly in this cycle, in the early part of the selloff in 2008 and 2009, you had credit spreads blowing out and government bond yields dropping. In corporate bonds at that time, you got a very muddled message.”

There was a subsequent “restoration of confidence,” but there is little scope left for more gains—as many investors have realised.

“If there is any major lesson, it is to look beyond the headline figures,” Frank says. “Credit spreads are pretty tight, equity valuations are high—how much further can these go?”

Ciaran Mulligan, head of manager research at Buck Consultants, agrees. “You could be happy with a 50% return, but there is more to it than that,” he says. “The seven-year period in question came pretty much from the top of the equity market rally of 2001 to 2007, when the MSCI World would have trounced 60/40. In 2008 through 2014, we had one of the biggest bull runs in equity markets ever, but it’s extremely unlikely that will extrapolate into the next few years. Diversifying from equities into bonds would have helped returns, but it’s a very specific part of history. Over the longer term, you would expect equities to do better.”

What of risk parity? The burgeoning trend of allocating to levels of risk rather than traditional asset classes is gaining traction—particularly in the US.

Mikulskis also charted the performance of a risk parity index run by Salient Partners, a US-based specialist. By this measure, risk parity trounced the opposition in the period under review with an 89.8% return. It was less volatile than the traditional mode, and its Sharpe ratio of 0.75 shows the best risk-adjusted return, with the exception of the bond index. The only downside is the downside: The risk parity index’s maximum drawdown of 19.4% was second highest after the MSCI World.

But, while the Hypothetical Pension Plan trustees should not stick with the traditional path, Buck’s Mulligan warns that risk parity can also under- and outperform.

“Risk parity often has more interest rate exposure than in the Barclays Global Aggregate Bond index,” adds Frank, indicating that investors should be wary of such strategies as central banks are expected to raise core rates and government bond yields are expected to increase.

Running 60/40 in the last decade wouldn’t have gotten you the sack necessarily, but you might want to start getting other ideas into that portfolio before it’s too late—regardless of any trustee reluctance.

As Redington’s Mikulskis puts it, a 60/40 portfolio “might have done reasonably in terms of returns, but going forward there are certainly many smarter things you can do.” A good line to push back at the Hypothetical Pension’s trustees, perhaps.

But it’s not just the old-fashioned portfolios that should heed the words of our consultant commentators. For anyone who thinks they came through the crisis period(s) unscathed, Mulligan has a few words of caution: “Going just on the last seven years is a dangerous game to play. You need to take the long-term view and not be swayed by immediate history.”

In other words: Well done for surviving the last seven years. Now get ready for the next seven—or more.