Here’s What Happens When a 27-Year-Old Finance Journalist Tries to Manage Money

“Do you plan on having children? Even if the answer is no, as a female of child-bearing age—for at least a few more years—you should recognize that pregnancy is a very real tail-risk event.” Oh God. Personal asset management advice feels like a phone call from my mother—if she had a PhD in financial economics.

This isn’t your typical financial planning

session. Institutional experts—the type who say ‘nine’ and mean $9

billion—don’t do sensitive. If you’re responsible for making ends meet on a $15

billion industrial pension plan, the best news you’ll hear all year is an

actuary saying “longevity assumptions declined under new guidance for blue-collar

demographics.” That means Grandpa Pensioner dies sooner. (You hope.) To these

investors, my ovaries aren’t an awkward topic. They’re a tail risk.

Liability-driven investing (LDI) is the antibiotic of corporate pension management. It’s mainstream experts’ standard prescription for treating a routine condition: A company’s pension plan is closed to new members, is in good financial health, and must pay promised benefits to every last retiree. In a post-LDI world, that’s a fixable problem. Like strep throat, it can also kill you if left untreated.

The philosophy is simple. “Invest so that the value of assets changes in line with changes in the value of liabilities,” a succinct definition from specialist Insight Investment. If traditional investment success is beating the market, winning at LDI is the freedom to forget about the market. Up or down, volatile or calm, pensions get paid. But just as importantly, everyone knows they’ll get paid. If GM’s CEO has to report a bad quarter to industry analysts, she wants weak SUV sales to be the reason—not suddenly unaffordable pension liabilities.

Investment strategies as a whole suffer from the ex-ante problem: They work until they don’t, and at that point, it’s too late. As every glossy money management brochure dutifully notes, “past performance does not guarantee future results.” Yet basic LDI keeps working more or less as promised—a unicorn in a hype-prone industry. Plan sponsors have noticed. Roughly three-quarters of corporate America’s legacy pension funds follow a form of LDI or plan to, according to the latest figures from Towers Watson and SEI. In the UK, adoption is even more widespread.

Specialist managers can (and do) get as fancy as they like with proprietary techniques for pairing pension assets with liabilities. But basic and effective LDI routinely succeeds at minor and unsophisticated funds, as well.

So how hard can it be?

From:

Kristopher McDaniel

To:

Leanna Orr

Subject:

De-risking story.

Sent:

September 9, 2015, 7:16am

Orr!

We’re

going to give you $1,000, and you’re going to write a feature (cover?) on the

humor/difficulty of actually trying to buy a portfolio that matches your

‘liabilities.’

Go!

—Kip

Oh s%*!. Liability matching… that’s

LDI right? So, long bonds—something about yield curves? Those things are like Anna

Karenina: Supposedly ‘foundational’ but no one actually gets further

than reading the Wikipedia summary… FOCUS ORR. OK, what are my liabilities:

Rent, MetroCard, cocktails, shoes. Is this real money? Can I just buy shoes

with it? Stiffs in the finance department would throw a fit. So bonds. Right.

How do I get a bond? Are Canadians in America even allowed

to own bonds without a green card? … I said FOCUS! Let’s take stock. Investment

experience: None. Current portfolio: 50% in default 401(k) option, 50% in

checking account. Real assets: MacBook Pro, fixed-gear bicycle, shoes.

Emergency assets: If truly desperate and cool with never working as a

journalist again, then whatever $$$ Lazy Asset Management Co. X

would pay for my Rolodex of institutional CIOs…

Wait. This is what Steve Cohen calls “edge”—except it’s not… you know. I don’t have a clue how to LDI myself. But I know plenty of people who do.

A remarkable panel of specialists stepped up as advisors, guiding me in assessing liabilities and desired outcomes. At this point, my best friend, doctor, and parents know less about my finances and life goals than Jodan Ledford (head of US solutions, Legal & General Investment Management America), David Eichhorn (managing director, NISA Investment Advisors), Mark Thompson (CIO, BP America), and Neil Olympio and Frank van Etten (advisor; head of client solutions, UBS Global Asset Management).

Their first piece of advice: Ask for more ‘money.’

“Do you want to hedge your current liabilities or future retirement liabilities?” Jodan Ledford, I am sorry you have the unlucky first interview. I don’t know what the ‘L’ is in my LDI mission. “It will be easier to get definitive responses from us on retirement,” he suggests. “Since it sounds like Kip won’t be funding you with real money, comparing and contrasting two portfolios might be interesting. One is meant to stabilize over the long term and grow now, and the other aims to hedge your present fixed expenses—which I assume are fully funded.” Check! I can totally pay my rent next month. #winning.

Two portfolios it is. For each, a cool $1,000 in liquid CIO pesos—pegged to the US dollar, naturally—ready to deploy at whatever the LDI gurus think will pay my bills and fund my retirement. Let’s do this.

“Look at the unintended consequences of assets that will help hedge each liability stream,” Ledford continues. “For present expenses, you don’t care about almost anything except inflation. You can’t hold equities, because on a month-to-month timescale you may not be able to meet your liabilities given certain markets.” Got it. No equities, all inflation hedging.

“For retirement, I assume you are very far from funded”—This guy’s good—“so you want to be holding lots of equities which will grow over time. In some years they’ll fall in value, but you’re young and can shift away from the exposure as retirement gets closer.”

So equities = Cushy retirement someday, potentially homeless now. Inflation-linked bonds = December rent paid, golden years in orange Home Depot smock. Corporate pensions’ dual-bucket strategy—one growth seeking, one liability hedging—makes so much sense!

“You can’t optimize for the two time horizons,”

Ledford concludes. “You’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t in both cases.

Nobody says this is easy.”

MasterCard (October): $1,531.89. MasterCard (September): $2,393.50. Nope, too volatile. Next. Cell phone: $0 (Thanks, employer!). MetroCard: $70ish. Rent: $750, with zero nominal volatility in 49 months and counting. It’s the closest to an actuarially predictable, diversified group of aging pensioners that I’ll find in my own budget.

“Manhattan rent… There’s not going to be an asset that’s highly correlated,” says David Eichhorn, NISA managing director, burster of bubbles, rainer on parades. “The biggest hedge you have is working in Manhattan. Your specific employer—Kip—may or may not keep up with median rent. But on average, employers have to or they don’t have employees. There is still a lot of company-specific risk on you. But other than some exotic levered REIT strategy—which would come with all sorts of other risks you don’t want—inflation-linked bonds may be the best option.” They are far from a perfect measure of personal liability inflation. My gas expenditure alone ($0!) put me off track from the consumer price index (CPI). But at least TIPS—Treasury inflation-protected securities—are accessible with a $1,000 portfolio, unlike that other popular rent-matching suggestion: Manhattan real estate. Seriously, asset managers. Advising a 20-something journalist to simply “buy an apartment in Manhattan” is why everyone thinks you’re overpaid. TIPS it is.

Continued from here.

Professional retirement hedgers, welcome to your chance for redemption. My long-dated liabilities present a problem every target-date fund manager swears they’ve solved—and it’s always with a ‘solution.’

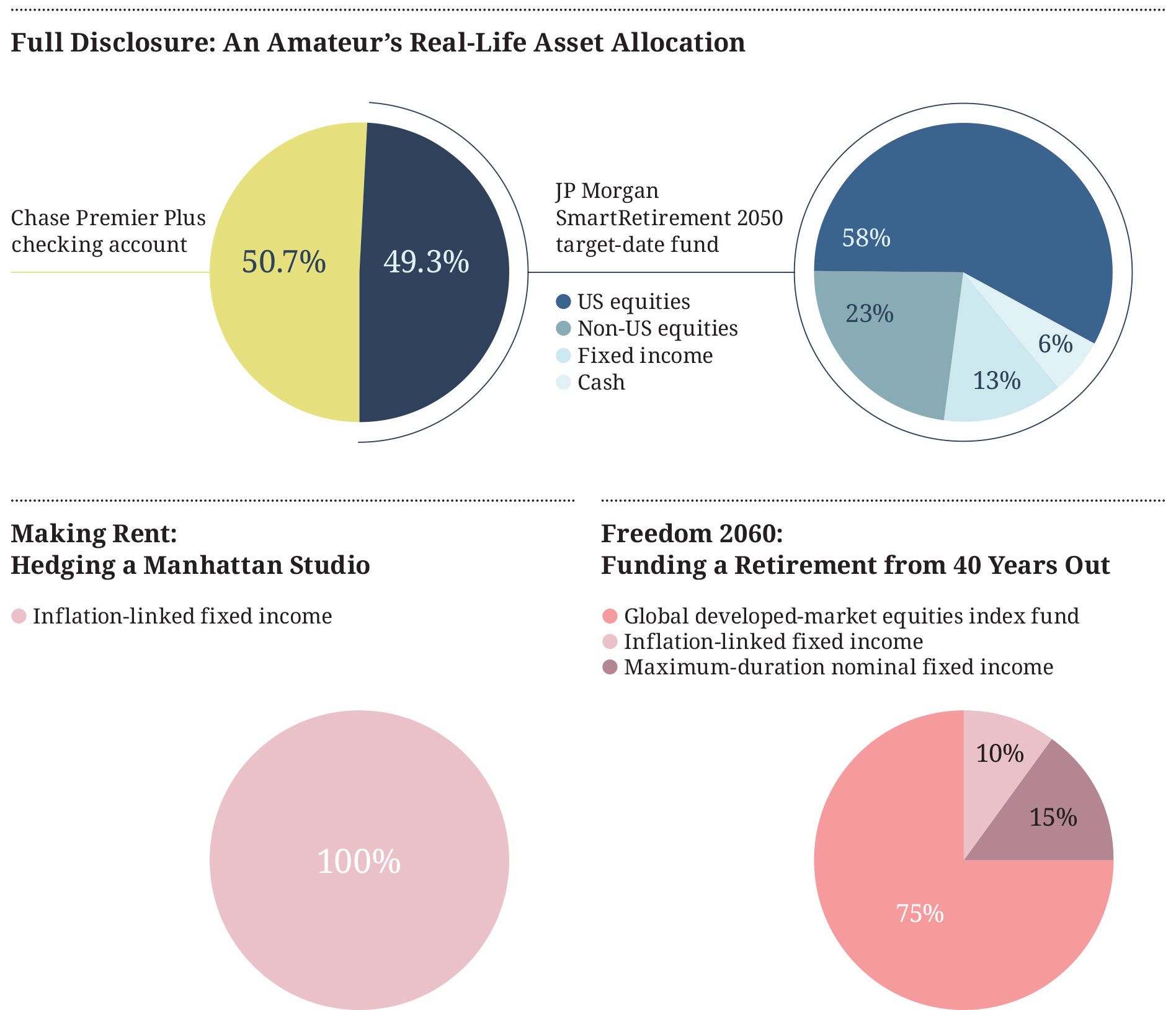

Indeed, half of my (real) assets are in a

target-date fund: JP Morgan’s SmartRetirement 2050, the default 401(k) option

for a 24-year-old joining Asset International Inc. in 2011. According to JP

Morgan, the portfolio optimized to fund my future life as a retiree is 58% US

equities, 23% non-US equities, 13% fixed income, and 6% cash. And by “my future

life,” I mean the retirements of any human Millennial employed in America whose

company picked SmartRetirement. Morningstar gives the fund a silver rating,

three stars, and a “low” fee level at 94 basis points. According to Milliman,

it lost 4.2% for the 12 months ending October 2015. Perfect.

Remarkably, without allocating a penny of my imaginary $2,000, I’ve already screwed up. Mark Thompson, BP’s CIO, points this out. We’re discussing the appropriate level of oversight and automation for a retirement portfolio, and I admit that all my houseplants have met with untimely ends. Then I stopped buying houseplants.

“I’d keep it simple,” Thompson says. “If you can’t keep a plant alive, how are you going to keep a portfolio alive?” True story. “I would say someone like you should look at your retirement account no more than once every five years.” Hence, mistake #1. “When the statements come in, stick them in a box or hide the emails. It’s not worth crying over. You’ve got at least 30 years before the ebbs and flows of the market will count against you.” By Thompson’s reckoning, my target date should be more like 2060 than 2050, but otherwise my investment strategy—doing nothing—is nearly on track. “Particularly as someone with a lot of years to go, I advise sticking your ‘windfall’ in the lowest-cost target-date fund you can find.”

JP Morgan SmartRetirement is too smart for my money, apparently. Active managers invest all of its $2.1 billion, according to Morningstar. “Passive equities on the domestic side will work for what you need, and if you want to spice it up, add emerging markets,” the CIO says. “As an individual retail investor, you’re not going to diversify your risk across enough active strategies to win.” JP Morgan already charges me nearly five times more than its lowest-fee passive competitor.

Fidelity Freedom Index 2050, prepare for a negligible amount of imaginary capital.

Fidelity Freedom Index 2050 doesn’t want my money. That tired cliché about not wanting into clubs that’ll have you as a member? Reverse it, and you have personal LDI. Fidelity’s bargain basement target-date fund requires a princely $2,500 minimum investment, pricing out the likes of me—right now, at least.

A 40-plus-year liability gives my capital 40 years to catch up to fund provider thresholds. It also gives providers 40 years to catch up with market demand for investable products. For example, one asset recommended by five out of five of my LDI guides doesn’t even exist yet. And even if it did, no one would sell it to me for another quarter-century.

The UBS de-risking duo of Neil Olympio and Frank van Etten gets my struggle. “You’re attempting to replicate with self-insurance the benefits of a pension plan,” van Etten clarifies. Is that an option? Yes, please. I’ll take one pension, thank you.

“In the end, just make sure that you’ve accumulated sufficient assets, which takes discipline.”“There are three things you need to protect against,” he continues. “One: Longevity risk. This is the risk that you live too long. How is that risk, you say? Because of number two: Shortfall risk. Your money gives out before you do. Mitigated by sufficient saving up until retirement and shifts in asset allocation over time.” Equities now, bonds later, minimal fees throughout, ramp up 401(k) contributions, taper footwear expenditure. I know the drill, and naturally show that off to Mr. van Etten.

“Three: Inflation risk. Not measured by CPI, but the actual expenditures that will make up your retirement liabilities. Foremost, you’re concerned with rising cost of health care.” Elderly inflation risk, meet your kryptonite: Canadian citizenship.

So, that leaves longevity. Beyond taking up smoking, what’s on the hedging menu?

“The only protection is an insurance product,” van Etten explains. “An annuity. Unfortunately, the products available are just not good enough yet.” Such is DIY LDI: Pair singular risks with their asset soul mates—as long as that soul mate is a stock, retail bond product, cash, or mainstream index tracker.

A guaranteed income product that begins payouts around age 80 or 85 “makes funding retirement tractable,” according to Eichhorn. “It creates horizon clarity over which your assets need to last.” He and his fellow LDI alchemists at NISA are at work on a viable annuity product for defined contribution members, but no provider has yet cracked that nut. He does seem confident one will arrive to market by the time I’d be an eligible buyer (roughly 2040). “You bear a very ill-diversified risk of your own longevity,” Eichhorn says. “This is a powerful way to cut that tail off.” Uh oh, back to the tail risks…

“Until then, hedge the future purchase by owning long-maturity fixed income,” he advises. “Think of this as laying bricks.” As we get deep in the weeds of guaranteed income replacement percentages (80% for a life of travel and comfort vs. 70% for bingo and early bird specials), Eichhorn pivots the conversation to a now-familiar warning. “This is all assuming you’ve saved enough to afford 80% replacement: If not, no investment strategy can help you very much.” Team UBS puts it more starkly. “In the end, just make sure that you’ve accumulated sufficient assets, which takes discipline,” van Etten stresses. So you’re saying the best hedge against future liabilities is having more money? He laughed. “Exactly.”

The very concept of self-LDI reframes a savings

problem as an investment problem. If the average closed corporate pension had

the same funding ratio as a typical mid-career American worker, LDI would be

confined to the wealthy fringe, the strategy of exotic 1%-ers. Because without

assets, there’s nothing to match.

Jodan, Mark, Frank, Neil, David: You can all relax and unpack those boxes and family photos. Your jobs are safe. Although none of you said it explicitly, I know how worrying the arrival of a disruptive new talent can be. But fear not. My foray into liability-driving investments affirmed to me that you are all magicians, I will not ever be able to retire, and should probably figure out how the damn yield curve works. For the sake of my 50% (real-life money) allocation to JP Morgan SmartRetirement 2050, please, please don’t leave us normals alone to single-handedly fund our highly idiosyncratic, tail-risk fraught, longevity-unhedgeable 0-to-40-year-duration retirement liabilities.

I tried. This is my second-best portfolio with $1,000 in Kip Coins:

● 75% global developed-market equities, passively invested in a broad and low-cost index fund.

● 15% nominal bonds, the longest duration I can get my hands on.

● 10% inflation-linked long-duration bonds, to begin “laying bricks” for the low-cost, high-value annuity product David and Co. will invent between now and

then.

But Frank van Etten, you were right all along. I don’t want a well-funded 401(k) to secure my retirement. I want a defined benefit pension.

Thus, my final portfolio: 100% to first-year tuition at a teachers’ college. By 2018, the fine citizens of Canada will be funding my retirement liabilities, in full, by law, and as far down that longevity tail as I can ride it.

To cap off my foray as CIO of an LDI-oriented imaginary family office, I diversified my bad-judgment risk and shared the strategy with van Etten.

Verdict: “……. Well. It probably works.”