Doing Private Equity in Public Markets

Invest in private equity for the return-smoothing, not the absolute returns, concluded Harvard Business School researcher Erik Stafford after attempting to DIY the asset class.

“Return smoothing is an acute concern.” Passive listed portfolios of small-cap value companies

—favored qualities of private equity firms—outperformed the average US private equity fund, both net and gross of fees. Stafford applied two turns of leverage to his replication funds, and backtested the strategy over 30 years (1986 to 2015).

Two stark differences emerged between the alternative asset class and its public copycat: Volatility and fees.

“The risks of the replicating portfolios are extreme,” wrote Stafford, the John A. Paulson professor of business administration at Harvard. His two listed models “experience a massive drawdown during the financial crisis of 2008, with both portfolios losing more than 85% of their value relative to their historical peak valuation.”

Compare that to a 20% drawdown in 2008 for Cambridge Associate’s private equity index, which Stafford used for the study. This was the largest drop for private equity since Cambridge began tracking industry performance in 1986.

With roughly half the annualized volatility of stock markets, private equity’s long-term risk-adjusted returns have topped nearly every other asset class.

But crediting managers with these results would be a mistake, Stafford argued. His study pointed instead to an accounting rule.

Private equity firms report performance based on the sale value of assets, a.k.a. book-value accounting, and highly malleable estimation. Listed portfolios mark their value to closing market prices, accounting for all the swings during ownership.

“Sophisticated institutional investors appear to significantly overpay for the portfolio management services associated with private equity investments.”Book-value reporting “significantly distorts portfolio risk measures,” Stafford wrote, calling into question “the strikingly attractive risk properties of the aggregate private equity index.”

To measure the impact of public-versus-private reporting methods on risk-adjusted returns, he recalculated the two listed replicas’ performance using book values.

“Remarkably, the worst drawdowns for the replicating portfolios with book-value accounting are only 15% and 7%, whereas the identical portfolios with market value accounting exceeded 85%,” the finance professor found. Absolute returns remained the same, of course: 21% and 19% annualized, while private equity gained 16% gross-of-fees.

After paying fees of roughly 6% per year, investors in private equity “are considerably underperforming the feasible alternative of investing in similar passive replicating portfolios.”

Listed portfolios cannot replicate all of the value-add avenues available to private-market managers—for example, improving operations—the author acknowledged.

However, Stafford concluded, “the results indicate that sophisticated institutional investors appear to significantly overpay for the portfolio management services associated with private equity investments.”

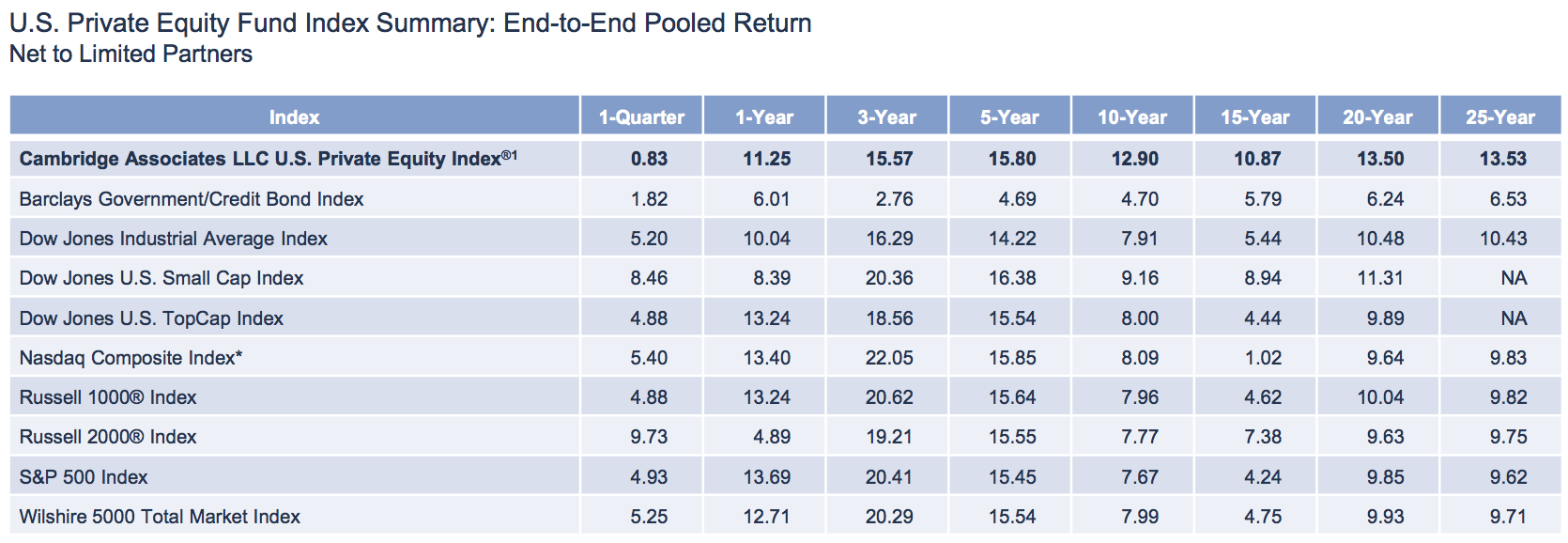

Source: Cambridge Associates, US Private Equity Report 2015 Q1

Source: Cambridge Associates, US Private Equity Report 2015 Q1

Stafford published the results of his study—“Replicating Private Equity with Value Investing, Homemade Leverage, and Hold-to-Maturity Accounting”—in late December.

Related: Private Equity Returns Waver After Three Years of Gains & The Argument for Private Equity