Two teenage girls, in leggings and $700 Canada Goose parkas,

took iPhone videos of 115 or so rain-soaked protesters from inside an Italian

market in Greenwich, Connecticut. “Oh my God!” they laughed. “Pay your taxes!

Hahaha should I hashtag ‘Payyourtaxes?!? Oh my God, look at this! It’s soooo

funny.”

Each demographic of Greenwich’s well-heeled set had a

characteristic reaction to the demonstrators. Like their teen daughters,

middle-aged women tended to treat the band of mostly minority 99%-ers as a

spectacle—but a potentially dangerous one.

“The people here can be… a little out of touch,” Greenwich

Police Department Captain Mark Kordick told me. “I had one woman in a brand-new

Porsche wave me over as the protest was moving down the main street and ask

me—and I quote—‘Is it safe to go shopping?’”

“So I said to her,” the 26-year department veteran

continued, “‘Lady, the only danger is going to be to your credit rating.’”

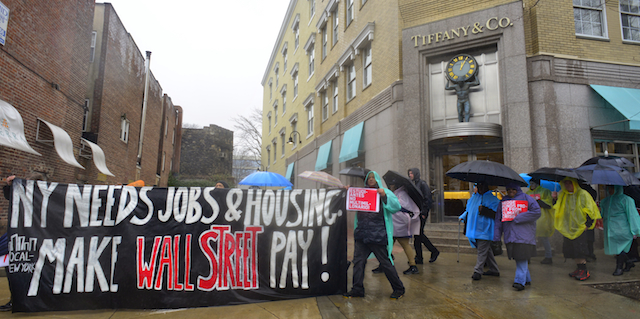

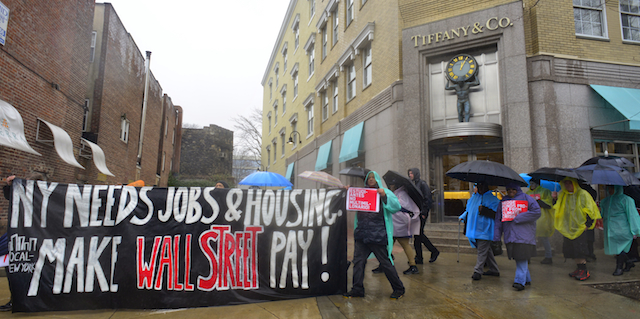

On the morning of Saturday, March 14, three busloads of

demonstrators pulled up to the glass-fronted Greenwich Public Library to “show

‘Hedge Fund Haven’ what angry working families look like.” A collection of

labor unions and community groups, under the banner of the Strong Economy for

All Coalition, helped organize the rally, dubbed the Hedge Clippers. No actual

hedges were harmed in the making of this demonstration.

Rather, dozens of largely underprivileged New Yorkers

marched from the library, rallied in front of the local JP Morgan outlet, and

proceeded down the luxury-shopping artery of Greenwich Avenue. Past Tiffany’s, Saks Fifth Avenue, and

countless cafes, they called on billionaires to “pay your fair share” and

proclaimed that the public education system is not for sale.

“We’ve seen around the country that hedge funds are not a

good deal for anyone—except the managers themselves,” organizer Jonathan

Westin, director of activist group New York Communities for Change, told me at

the rally staging ground. “They charge exorbitant fees literally from working

families’ money. That shouldn’t be allowed. We’ve seen Warren Buffett question

their effectiveness and hedge funds dropped by the largest pension fund in

California”—also in America: the California State Public Employees’ Retirement

System. “We’d love to see New York pensions do the same.”

Photo: Caleb OberstFor no clear reason,

the Hedge Clippers protest targeted Paul Tudor Jones, billionaire founder of

the private asset manager Tudor Investment Corporation. After the march down

Greenwich Avenue, demonstrators regrouped and bussed roughly a mile to Jones’

gated community of Belle Haven. Although some media outlets reported that he was

“the target of protesters on his front lawn,” police at the scene told me, “we’re

not even close. You can’t see his house from here.”

Photo: Caleb OberstFor no clear reason,

the Hedge Clippers protest targeted Paul Tudor Jones, billionaire founder of

the private asset manager Tudor Investment Corporation. After the march down

Greenwich Avenue, demonstrators regrouped and bussed roughly a mile to Jones’

gated community of Belle Haven. Although some media outlets reported that he was

“the target of protesters on his front lawn,” police at the scene told me, “we’re

not even close. You can’t see his house from here.”

Organizers gave the conflict between Jones’ Robin Hood Foundation—dedicated

to ending poverty in New York City—and his reported $500 million spend on

politically-tied organizations since 2000 as the justification for the targeted

rally. By Hedge Clippers’ own analysis, his donations pale in comparison to

Third Point CEO Daniel Loeb’s (upwards of $1 billion) or Tiger Management

founder Julian Robertson’s ($1 billion). But like any good journalist knows,

nothing carries a message like a narrative, and every story needs a villain.

Paul Tudor Jones’ demographic—the older, moneyed white men

of Greenwich, Connecticut—showed no amusement at the dozens of poncho-clad

protesters who took over their streets on Saturday. From the front table at a

café, two of these sort sat eating lunch as the demonstration moved past. Over

the back of one’s chair hung a McLaren Formula One racing jacket. Turning to

look at the passing protest, it was clear he had no desire to hashtag the

event. Likewise, the driver of a luxury SUV, forced to interact with

demonstrators walking along on a narrow Belle Haven road, pushed past with his

eyes locked straight ahead.

“It’s like we’re invisible,” a soaked woman with long dark

curls said to me, shaking her head. “They won’t even look at us.”

Ask any institutional

CIO what the worst part of their job is, and you’re likely to hear the same

answer: Politics.

No one becomes an institutional investor to play diplomat or

legislative booster. “Balancing the needs of many stakeholders”—an

on-the-record CIO’s euphemism for the P-word—is the price many pay to practice their

art: balancing a portfolio and the financial needs of an institution. Demonstrations

like Hedge Clippers count as one more signal of political pressure—particularly

those for those in the public sphere—that threaten to undermine institutional

investors’ mission of achieving the best risk-adjusted returns for members.

Many hedge funds and private equity operations have

performed spectacularly in this respect. Down the road from Greenwich in

Westport, Connecticut, Bridgewater Associates earned an estimated $36 billion

for institutions invested in its Pure Alpha fund between 1975 and 2012. Jones’

flagship fund, Tudor BVI Global, has returned nearly 19.5% annually. Former New

York City Retirement Systems CIO Larry Schloss favored hedge funds for

institutional portfolios because of their very structure. “My definition of alignment is, 'How much money can the

manager lose when I lose?',” he told CIO

in 2013. Unlike traditional asset managers, with alternatives the answer is “a

lot.” Perhaps everything.

Photo: Caleb OberstBut asset owners are also true experts in incentives. They

meticulously devise compensation structures to

maximize alternatives managers’ desire to perform. What CIOs never mention is one of

the largest incentives driving American hedge fund and private equity managers

today, and something that’s also among the protesters’ biggest complaints: the

carried interest tax. For individuals in alternative asset management, this

federal law caps taxation on long-term investment gains at 20%. If it disappeared,

as the Hedge Clippers shouted for on Saturday, managers would see their profits

cut nearly in half. Anyone making more than $432,201—a.k.a. any successful

manager—would fall into the top federal tax bracket and pay 39.6%. Relative to

almost anything else, hedge fund and private equity professionals have the

highest incentive to protect this rule—or loophole, as some refer to it.

Photo: Caleb OberstBut asset owners are also true experts in incentives. They

meticulously devise compensation structures to

maximize alternatives managers’ desire to perform. What CIOs never mention is one of

the largest incentives driving American hedge fund and private equity managers

today, and something that’s also among the protesters’ biggest complaints: the

carried interest tax. For individuals in alternative asset management, this

federal law caps taxation on long-term investment gains at 20%. If it disappeared,

as the Hedge Clippers shouted for on Saturday, managers would see their profits

cut nearly in half. Anyone making more than $432,201—a.k.a. any successful

manager—would fall into the top federal tax bracket and pay 39.6%. Relative to

almost anything else, hedge fund and private equity professionals have the

highest incentive to protect this rule—or loophole, as some refer to it.

As much as asset owners broadly wish to keep out of these

debates, if they’re paying performance fees as they so hope to, it’s only

reasonable to expect that some of their managers are also paying to protect

their own interests. In that sense, institutional capital allocated to

alternatives cannot help but be political, putting asset owners on a proxy

collision course with the likes of the Hedge Clippers.

Photo: Caleb Oberst “I wasn’t making $1

million a day, and I paid 50% taxes,” retiree Anslen Carter, 69, told me as

the rally wrapped up. “I spent 27 years working in aircraft maintenance at John

F. Kennedy Airport. If we don’t pay taxes, we go to jail. These guys hardly pay

taxes, and they get to live here. They’re legal crooks.” Carter shook his head.

“It’s not fair.”

Photo: Caleb Oberst “I wasn’t making $1

million a day, and I paid 50% taxes,” retiree Anslen Carter, 69, told me as

the rally wrapped up. “I spent 27 years working in aircraft maintenance at John

F. Kennedy Airport. If we don’t pay taxes, we go to jail. These guys hardly pay

taxes, and they get to live here. They’re legal crooks.” Carter shook his head.

“It’s not fair.”

If events like the Hedge Clippers protest point to larger

trends, alternative investing’s entire incentive system—and asset owner’s place

in it—could undergo a revolution come the 2016 US Presidential election.

But Police Captain Mark Kordick has seen this all before. “We’ve

been getting protesters here since the ’80s,” he said as he drove me and my

photographer back to the library, marking the first (and hopefully last) time a

CIO employee has been in the back of

a cruiser on the job. “The gated communities don’t like it, but there’s not much

they can do: It’s public property.” I asked what he thought, as a public

employee, of pension money bankrolling the Belle Haven estates.

“Funny you should ask, because for the last 14 years I’ve

been an employee representative to the city’s $400 million pension board,”

Kordick said. “Technically we don’t have allocations to true alternative

investments—but that’s not to say I’m averse to it. We invest the money in a

way to solely maximize returns on a risk-controlled basis. Now get out of the

car.”

Photo: Caleb Oberst

Photo: Caleb Oberst Photo: Caleb Oberst

Photo: Caleb Oberst Photo: Caleb Oberst

Photo: Caleb Oberst