Art by Kyle SteckerHow long did it take you to choose your current home? After

you looked at the neighbourhood’s schools and transport links, considered

whether you wanted a modern or traditional home, you may have even thought

about how the furniture from your old house would fit the new.

Art by Kyle SteckerHow long did it take you to choose your current home? After

you looked at the neighbourhood’s schools and transport links, considered

whether you wanted a modern or traditional home, you may have even thought

about how the furniture from your old house would fit the new.

Now compare that with how long you spent inspecting the pipes that would bring fresh water to your family each day and ensure your house is heated for the winter. Or the electrical circuits to keep the lights and internet on.

Probably much more on the former, right? The same is true in investing.

Asset/liability studies, portfolio allocation, even selecting a fund manager, these are the usual tasks that fill the days of a CIO or pension fund investment team. Much is written about how to tackle them, advice from all corners is readily available, and people argue constantly about the best way to squeeze those extra returns from a portfolio.

But all this good work can be undone if enough attention isn’t paid to the operational efficiency of the institution. Is anyone looking at your average VWAP (volume-weighted average price)? What about your TWAP (time-weighted average price)?

It’s unlikely that more than only a few of you have considered implementation shortfall, but there is someone willing to do it for you—and more are joining the line to offer help.

As investors are bringing more investment decisions in-house, more of the asset management processes are moving under the same roof as well. Combine that with the onslaught of regulation coming from the major financial watchdogs, and CIOs (and their staffs) could be forgiven for pining for the old days when Asset Manager X constructed a balanced portfolio for the fund before everyone retired to the golf course.

Instead, major pension funds are teaming up with custodians, investment banks, and other third parties to help their households run efficiently.

The UK’s £21 billion Railways Pension Scheme (Railpen) recently restructured and took direct ownership of more investment decisions to add to its already significant in-house set up. Despite being the sixth largest pension fund in the UK, it had, until last year, relied almost exclusively on external investment managers.

As part of this move to internalise investments, the pension appointed Northern Trust to provide trade matching, derivative processing, lifecycle management, active collateral management, and book-of-record services.

“The in-house model allows us to reduce implementation costs and ultimately return value to the scheme and members,” says Nicola Dymond, COO for investments at Railpen. Northern Trust’s appointment “gives us timely access to operational scale and breadth of capability without the associated capital expenditure,” she adds.

Additionally, the pension appointed BNP Paribas Securities Services to manage its dealing “to optimise the execution of its market transactions,” according to the French bank.

“Some asset owners who manage their own money are facing the very high costs of maintaining and upgrading their operational architecture, while they also have issues around know-how and manpower,” says Philippe Boulenguiez, head of dealing services at BNP Paribas Securities Services.

“Pension funds need to fulfil obligations from new trading regulations around best execution,” adds Boulenguiez. “The asset management community has already moved forward with this and now pension funds managing money internally will have to tackle the same challenge. Accessing liquidity has become more of a challenge for all investors.”

This additional burden weighs heavy on those who move assets in-house to streamline (and cut the cost of) operations. If market participants who have been managing third-party assets for decades are moving heaven and earth to keep up with the changes, these latecomers are bound to need some help.

But it is not as simple as just buying a product off the shelf.

“Investors need to work on their own vision and ambition, which might mean excluding certain investments,” says Marcel Prins, COO at APG. Prins oversees the investment operations for the world’s second largest pension fund, ABP, which is APG’s main client. “A provider might want to sell us something—but it has to fit what we, and our clients, want,” says Prins. “And we are also aware that we cannot do everything at once. We have open dialogues with providers—taking in the views of everyone involved—and decide whether it is more efficient to make or buy what we need.”

Risk management dashboards, value-at-risk controls, liquidity management software…

They are just the tip of the iceberg with banks and other service providers spotting

a gap in the market.The time was that custodians, banks, and other providers

of non-fund management services would offer various ancillary services for

nothing if an investor took their main product. Those days are gone, according

to Maurice Mulders, manager of portfolio administration at PGGM, which runs the

assets for the €180 billion PFZW in the Netherlands.

“Institutional investors are looking for low cost and transparency,” says Mulders. “In the past, parties would provide services and price these as a part of the whole service. This sometimes resulted in losing out on one service but having the profit on another service. With a greater transparency this is not a sustainable environment.”

Despite having size on its side, PGGM strives to attain that sustainability by negotiating a fair price for all services, according to Mulders—an argument that is echoed by APG’s Prins.

And providers realise it’s likely to be more profitable to partner long term with these investment giants than try and make a quick buck. “Service providers welcome this transparent approach,” says Mulders, “since this is helping them to single out hidden costs in their own organisation and creating a sustainable chain in the financial system.”

For investors who have not yet taken the plunge to bring operations as well as investment decisions in-house, or maybe never will, there are also plenty of developments happening for them too.

State Street’s transition management team has created a product to make the process of transferring assets from one fund manager to another as smooth as possible.

The bank steps in to oversee the assets from the moment a CIO or trustee board sign off on a new investment mandate. Using a system of futures, overlays, and passive investment products, the bank will manage the risk from the word ‘go’ rather than watch a portfolio suffer the ups and downs of the market before switching managers.

Cantor Fitzgerald has also joined the transitions party with a host of services that goes even further. The investment bank will allow clients to engage for services either through its asset management or brokerage arm, as they see fit, for transition and other ongoing risk management services. Cantor will then either trade what is needed from the portfolio itself, or utilize an external multi-broker platform, according to the clients’ wishes.

Risk management dashboards, value-at-risk controls, liquidity management software… It’s likely most large investors have already signed up for at least one of these services—and they are just the tip of the iceberg with banks and other service providers spotting a gap in the market.

“People suggest many new products to me,” says APG’s Prins. “But I also talk with other pension funds on a regular basis—both in the Netherlands and internationally—about how to lower costs for all of us. There is a lot of technology ahead.”

Making such significant changes to how a pension is run is no small feat, but there is help out there to smooth the road—for a fee, of course.

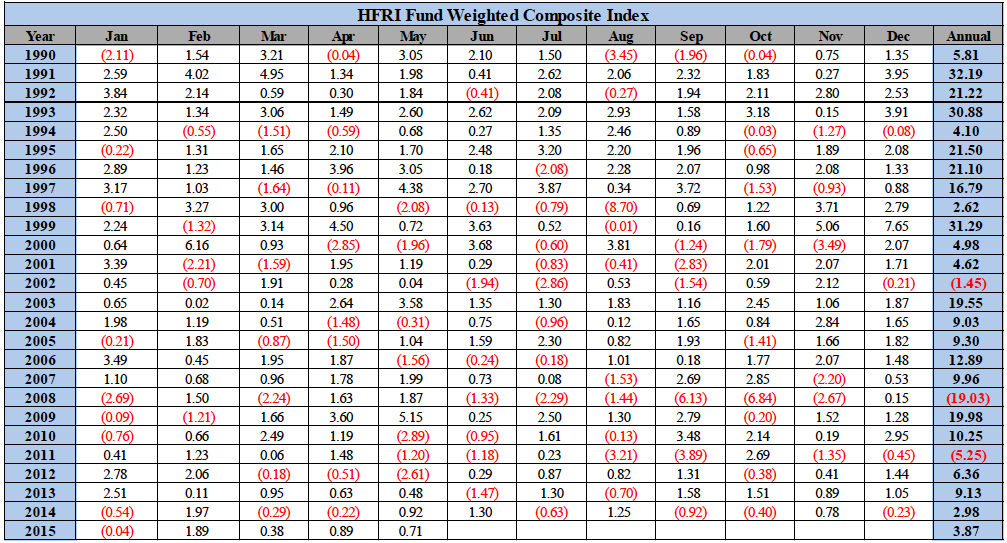

Source: HFR

Source: HFR