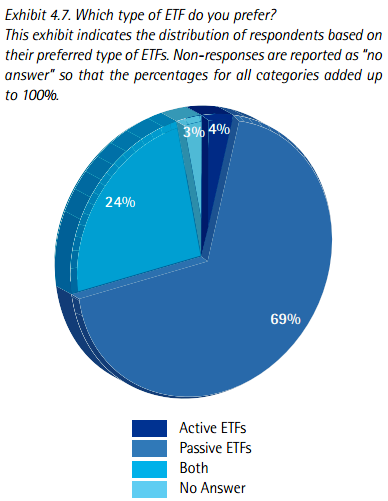

Investors overwhelmingly prefer passive exchange-traded funds (ETFs) to their active counterparts, a survey has shown, despite many asset managers latching on to this new option.

Just 6% of respondents to EDHEC-Risk Institute’s annual survey—conducted with Amundi Asset Management—said they preferred active ETFs to passive vehicles. In contrast, 70% preferred passive vehicles with just 22% having no preference.

The lack of enthusiasm for these new products may be caused

by a dilemma that is inherent to their nature, the survey said.

The lack of enthusiasm for these new products may be caused

by a dilemma that is inherent to their nature, the survey said.

“Active ETFs are supposed to have some of the advantages of ETFs, such as transparency, tax efficiency, and liquidity, all while being actively managed,” the report stated. “However, since managers are paid for their stock selection, frequent disclosure of the underlying stock holdings would encourage other investors to buy the underlying securities on their own instead of trading ETFs. On the other hand, if transparency is low, the price of ETFs would suffer significant deviation from the net asset value of the underlying holdings.”

EDHEC said many ETF providers in the US had made applications to the Securities and Exchange Commission to launch actively managed ETFs that would not disclose their holdings on a daily basis, but have not been permitted to do so by the regulator.

“This may illustrate the conflict between the product providers’ desire to keep their investment strategies private when it comes to active management and the regulators’ efforts to maintain the key property of transparency within ETFs,” the institute said.

Despite the efforts from some fund groups intent on launching new actively managed products, the percentage of investors showing a preference for them has remained the same, the survey showed.

PIMCO launched the Total Return Active ETF in March 2012 and within eight months it was the largest product of its kind, with $3.4 billion in assets. However, compared to the traditional fund it was set up to mirror, it has less than 3% of the assets.

“Innovations of ETFs should catch up with the innovations of indices.” —EDHEC Risk Institute“Actively managed ETFs are indeed not as important to our respondents and only 16% think that ETFs should shift from passive to active,” the survey concluded. “This percentage is quite stable through the years (18% in 2013, 17% in 2012).”

There is one area where asset managers should instead be looking, the survey suggested.

“We can also see that 38% of respondents find it important for ETFs to track niche markets,” it said. “In other words, innovations of ETFs should catch up with the innovations of indices.”

At the top of investors’ agendas for these niche products were emerging markets and smart beta ETFs.

Related content: The Smart Beta Debate: Is It Active or Passive? & The Disappointment of Hedge Fund ETFs