Most backtests published in finance journals are wrong, a quantitative research specialist from Guggenheim Partners has argued.

The tool is as popular with finance academics as is it misused, according to Marcos López de Prado, a senior managing director, which “may invalidate a large portion of the work done over the past 70 years.”

“You never see a bad backtest. Ever. In any strategy.” —Josh Diedesch, CalSTRSLópez de Prado—who holds two doctorates in the subject and a research fellowship with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory—has been sounding the alarm on the “pseudo-mathematics” of backtesting for several years.

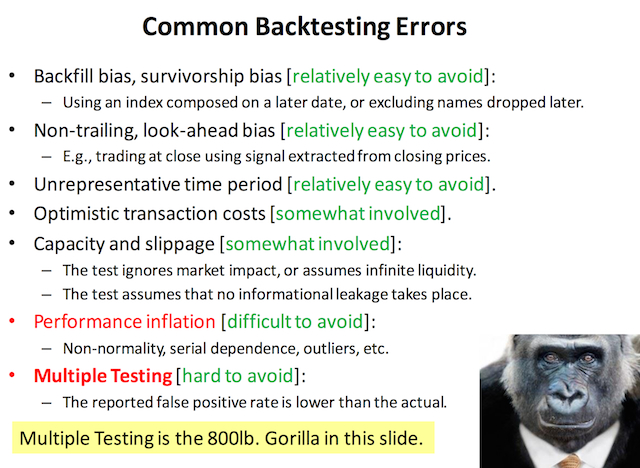

In a recent presentation, he singled out a common and critical error he said undermines the majority of research based on historical simulations: multiple testing.

This involves running multiple configurations of, for example, a theoretical asset allocation through a set of past market data then picking one to highlight. The practice poisons the selected results with selection bias, he said.

The American Statistical Society has voiced the same concern in its ethical guidelines.

“Selecting the one ‘significant’ result from a multiplicity of parallel tests poses a grave risk of an incorrect conclusion,” the guidelines stated. “Failure to disclose the full extent of tests and their results in such a case would be highly misleading.”

Grave critiques of backtesting are nothing new to institutional investing. Yet asset owners have tended to focus on managers’ use of the technique in marketing products, such as trumpeting phenomenal modeled performance over bizarre time spans.

“Backtesting: I hate it—it’s just optimizing over history,” California State Teachers’ Retirement System Investment Officer Josh Diedesch told CIO last year. “You never see a bad backtest. Ever. In any strategy.”

And according to López de Prado, academics are just as guilty of the practice as asset managers.

Read Marcos López de Prado’s presentation slides and, for a more in-depth discussion, his paper “Quantitative Meta-Strategies.”

Source: Marcos López de Prado’s 2015 presentation “Backtesting”

Source: Marcos López de Prado’s 2015 presentation “Backtesting”

Related Content: The Most Dangerous of Ideas: Unquestioned Academic Conclusions & The World’s Longest Backtest