[A version of this story will appear in the December issue of Chief Investment Officer.]

By the time you read this sentence, Russell Investments may

be no more.

If you read this in November, Russell will likely

remain what its official biography claims it to be: an industry-leading asset

management and servicing business with a global reach but humble Seattle roots.

If you read this in December or beyond, that may

not be the case. Sometime that month, insiders say, the London Stock Exchange

(LSE)—which in June purchased the firm from Northwesternern Mutual for $2.7

billion—will decide whether or not it wants to sell everything but Russell’s

vastly profitable index business. According to multiple former and current

Russell employees, this is exactly what it plans to do.

In this scenario, a quick auction will see a

private equity or non-American financial firm, looking for a foothold in the US

market, take over the venerable remains of Russell.

But whenever you read this, what you’ve been told

about Russell Investments—its history, its people, its place in the market, and

its future—is wrong.

(Art by Jon Han)

(Art by Jon Han)

So what is Russell Investments?

According to the official version, Russell is four

things.

It is a large and global consulting business,

although one that is no longer accepting smaller clients and that the firm

prefers to downplay in its marketing and public relations efforts. It has $2.4

trillion in assets under advisement, gathered over four decades in the

industry—an industry, according to company lore, that George Russell (grandson

of founder Frank Russell) pioneered.

It is an investment manager. Besides defined

contribution, multi-asset capabilities, and liability-focused expertise, this

includes an outsourced chief investment officer (OCIO) service for

institutional investors. By most measures, its OCIO business is the world’s

largest, ranking ahead of SEI and Mercer in total assets under control.

Overall, it manages $256 billion.

It is a

portfolio implementation business, offering transition management, currency

operations, and other trading services under the banner of Russell

Implementation Services (RIS). Polls of transition management users, including

surveys by this magazine, have Russell consistently outpacing its competitors,

admired for honesty, transparency, and performance. RIS’ other execution

services are equally well respected.

And it is an

index business. Born in 1984, Russell’s indices measure manager performance and

dominate the American equity benchmark market. Globally, $5.2 trillion are

benchmarked against them.

The unofficial

version of Russell is different.

“They are known

as a consulting firm. They are not a consulting firm,” says someone familiar

with Russell’s consulting business. (Russell declined to comment for this

story.) “The consulting arm is great for Russell’s brand, but it’s not a

leverageable business.” At its core, insiders say, consulting is an enabler of

other business lines.

It’s not just

Russell facing such problems, this individual believes. Consulting “won’t ever

be a high margin business for Russell or any other consulting firm,” he says.

“You can even argue that it’s not very profitable at all—but you keep it

because it gives you brand awareness, the ability to talk to smaller

institutions, distribution, and a quality of research. It’s a story that

resonates very well, but it’s just not a moneymaker. Absolutely, it will

survive—it just won’t thrive.”

What consulting enables are Russell’s other

service branches such as OCIO, although there is a misalignment of sorts,

according to another informed source. “Outsourcing, trying to take over the

whole fund, is not going to happen at the larger end, which is where Russell

traditionally consults,” he says. “For small or midsize funds, it can work.”

It’s also an enabler for RIS. Automation and fee

pressures—transition management, for one, is “a business where margins are

shrinking and players are exiting”—have this sector under pressure, according

to one of the firm’s competitors. RIS employees also reportedly face an

identity crisis: They are “thought of internally as an investment function, not

just a trading function,” one insider says. “Whether this is the way they

should be thought of is another matter.”

And then there

is the indexing business. Consulting does little to enable this $170 million

revenue stream, which houses just 130 of Russell’s 1,800 employees. While

Russell might disagree, multiple observers note that of all four businesses,

the indices could most easily be run as a standalone business without

suffering.

The sale itself

has hamstrung the daily operations of these four business lines, both in the US

and globally.

The OCIO unit,

for one, has been damaged by the uncertainty surrounding Russell’s future.

“When it comes down to three OCIOs in the finals of some deal, it’s tough to be

Russell right now,” one competitor says. “When you get to the final three, in

reality very little differentiates them. If a small endowment investment

committee has to choose between three firms they see as largely the same, it’s

going to be way easier to just kick out the one with the uncertain ownership

and future.”

Uncertainty has

shaken the global business, as well. For example, the firm’s Australian

arm—which by some estimates contributed approximately 5% to 10% of Russell’s

global revenue at its peak—has suffered. Two senior ex-employees in the region

recently acknowledged that while “consulting was always generally known to be a

gateway for the other business lines, they have lost a lot of their clients

recently.” Towers Watson has been the beneficiary of Russell’s troubles, they

say. These two do not believe the losses will be reversed. “There are no

shortage of Russell résumés in the market,” one says.

LSE is not buying the official version.

This became clear on June 26, the day that the

acquisition was announced. In a hastily organized analyst call, LSE Chief

Executive Xavier Rolet and CFO David Warren spent 17 minutes explaining the

benefits of combining LSE’s FTSE index business with that of Russell, while

only briefly paying lip service to the asset management division. This was

despite the reality that the division contributed 82% of Russell’s 2013 net

revenues.

About the only thing they would say about

Russell’s primary business was that they were commissioning a “comprehensive

review” of how it might fit into LSE’s current, and decidedly non-asset

management, structure. (Connecticut-based investment management consultant

Casey Quirk is conducting the study.)

For the remaining 38 minutes of the call, the

analysts—in the politest way possible, given their mostly British

accents—attacked. Representatives of Barclays, Bank of America Merrill Lynch,

UBS, HSBC, RBC, and others repeatedly brushed over the benefits of the indexing

merger and focused on investment management. The two executives’ responses were

always the same: Little comment beyond “comprehensive review.”

Did they really see themselves as an asset manager

in five years time, one analyst asked?

“Comprehensive review.”

Were there elements of the investment management

business that fit better than others?

“Comprehensive review.”

Were there any synergies between the asset

management unit and LSE?

“Comprehensive review.”

And so on. When pressed, Rolet and Warren directed

analysts to wait on an August circular that they claimed would offer further

insight.

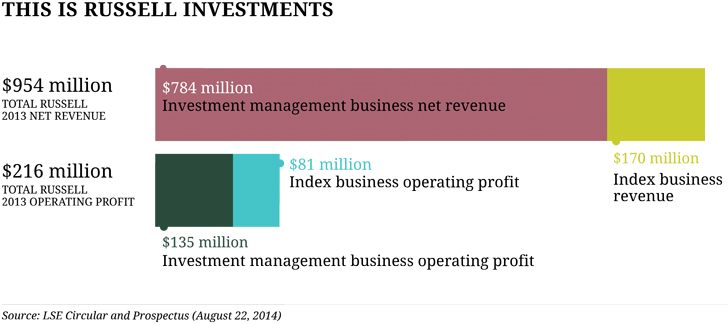

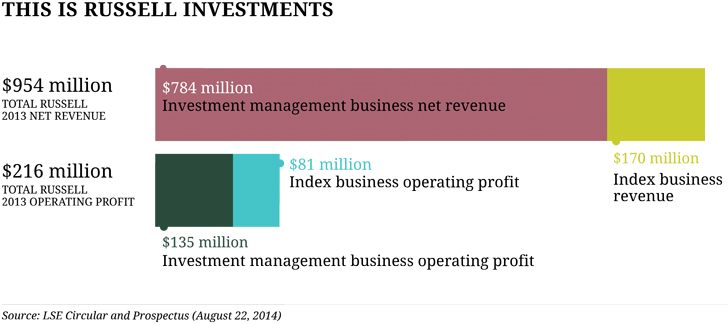

When the circular came out, analysts and anyone

else could see just how badly LSE wanted Russell’s indices. In 2013, the

service line earned $170 million in revenue, the document revealed. The rest of

Russell brought in $784 million, net of fees paid to third party managers

(reportedly substantial). Of this, insiders estimate that approximately $100

million originated from RIS, $40 million from consulting, and the remainder

primarily from investment management (IM). Unsurprisingly, profits skewed

towards indexing: operating profit for that business line neared 50%, while the

rest of the company hewed closer to 17%, according to the circular.

Also embedded within the circular’s listed risks

was this: “After completion, the enlarged group expects to separate the IM and

index businesses of Russell as part of the integration of Russell’s index business

with LSE’s operations.” LSE, as expected, declined to clarify whether this

implied a sale of the investment management arm. LSE also refused to comment on

other matters raised in this article.

Yet there is wide speculation that LSE will sell

the consulting and asset management units to either a strategic buyer or a

private equity firm. Multiple private equity principals, none of whom were

willing to speak on the record, admitted to preparing bids for the non-indexing

businesses. “It is generally acknowledged that they will soon be up for sale,”

one principal recently said.

Goldman Sachs—one of Northwestern Mutual’s bankers

on the sale to LSE—“had more than 100 interested parties who wanted into the

original process,” one person familiar with the original sale says. “They

narrowed it down and ran a fairly efficient auction.” Not all 100 will want the

asset management and consulting business on its own, but some certainly will.

“In this case, LSE can go to a narrower group. I would not expect a quick deal

with private equity or a strategic, though—they wouldn’t just do that deal

without a broader process.”

“They can be separated—and they are truly separate businesses,” one person intimately acquainted with Russell says. “Len Brennan”—the current CEO—“believes differently, and has tried to keep them integrated.”

Despite an apparently successful sale,

Northwestern Mutual has also drawn criticism for its oversight of Russell since

the 1999 acquisition. “It was poor governance on the part of Northwestern

Mutual not to have insisted that the business units be run separately enough

that they could be sold separately,” another person involved with the sale

process says. “They left a lot of value on the table in not doing that. Hardly

anyone wanted the whole thing—so they severely limited the universe of buyers.”

The universe of buyers could now be LSE’s concern,

of course. “All told, the consulting, asset management, and RIS businesses

could be sold for about $1 billion, if that’s what they choose to do” the

source says. That’s not pocket change, but the math on the $2.7 billion sale

price is striking: $1 billion for 82% of Russell’s business by revenue implies

a valuation somewhere near $1.7 billion for the 18% of revenue brought by the

indices.

“They can be separated—and they are truly separate

businesses,” one person intimately acquainted with Russell says. “Len

Brennan”—the current CEO—“believes differently, and has tried to keep them

integrated.” If a strategic buyer steps in, multiple insiders suggest Brennan

may stay. If a private equity buyer intent on cutting costs wins an auction,

his future is less certain. Either way, sources say, “he probably has the

financial freedom to choose.”

LSE and its management team are near universally

respected, garnering fierce loyalty from shareholders. And yet Rolet and Warren

bought Russell, nose-to-tail. Does LSE actually want to enter the asset

management market, as one analyst on the June 26 call so skeptically asked? Or

was purchasing the whole package the price of creating a global indexing

business?

The consensus is that it was. Analysts on the call

acknowledged the “obvious” benefits of merging the FTSE and Russell index

operations. Indeed, should the marriage sour, these analysts’ eagerness to

accept the theory could prove embarrassing.

The investment management business is itself a

quality asset, one former employee points out. “It’s just that it’s not what an

index provider would want.” LSE bought it, she and others speculate, because

that was the easiest way to acquire Russell’s indices—and because they knew

that they could eventually split off and sell it. (This outcome can be viewed

in the same light as the recent spate of corporate divorces—HP’s cleaving

hardware from servicing, for example—one source muses.) Analysts may have

initially been puzzled, but most insiders agree that if LSE succeeds in

decoupling Russell, it may have executed a masterstroke.

Any buyer of the non-index division takes on a strong

upside. The business runs at margins near 15%. For typical asset management

firms, margins are much higher. “This doesn’t mean it’s not a good business,”

says one person in touch with the firm’s inner workings. “It’s just been

allowed to run at a lower margin than it should. LSE could change that. But

will they?”

(Art by Jon Han)

(Art by Jon Han)