As a city, London has never been shy about its ambitions. First a seat of power over a vast global empire, one square mile on an island nation became a centre of global finance. London has, for centuries, punched above its weight.

On its 2015 agenda is one of the most ambitious collaborative pension projects ever seen. If these city schemes pull it off, they will achieve something many have attempted before—and all have failed at.

London has an estimated gross value added—the municipal GDP equivalent—of $836 billion (€742 billion), according to the Brookings Institution, and accounts for roughly a third of the UK’s economic output. The city’s asset management industry is one of the biggest in the world, home to some of the most famous (and infamous) financial brands.

But despite a reputation for financial expertise and innovation, London’s public-sector workers belong to one of the most fragmented—and arguably inefficient—pension systems anywhere. More than £25 billion (€34 billion) spreads thin across 33 local borough funds. Only three oversee more than £1 billion. Together, they paid more than £76 million in investment expenses in the fiscal year 2014, according to the funds’ annual reports—much to the vexation of the country’s ruling elite.

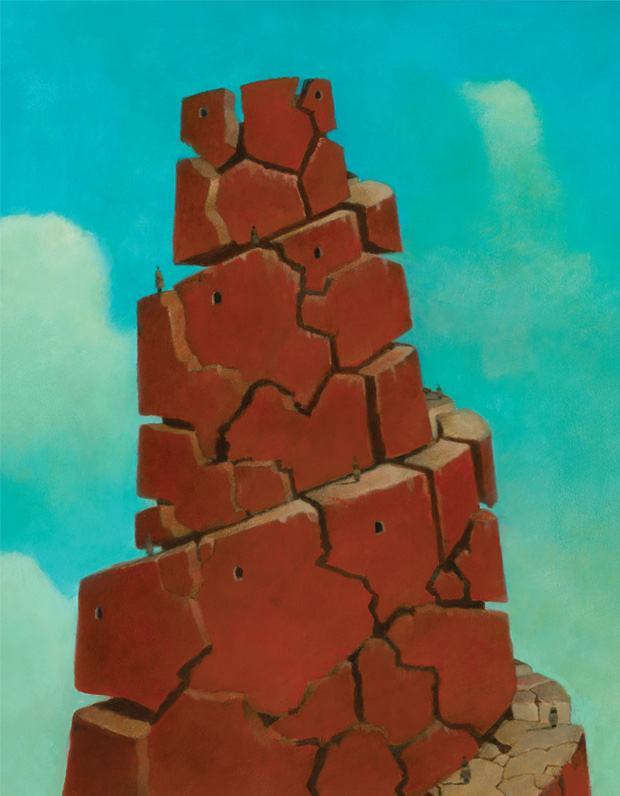

Half a century has passed since these boroughs came into being. As an anniversary gift—Brits not being known for their romantic sensibilities—a small team is embarking on a project to pool some of these billions. If the mission succeeds, it could open up new investment opportunities while cutting fees paid to those managers whose towers dot the London skyline.

Art by Brad Holland

Art by Brad Holland

“The one thing I said I didn’t want to be involved with was pensions,” says Hugh Grover of his appointment as policy director for local government finance at London Councils in 2009.

Grover meets CIO in a typical municipal government office: clean but sparsely decorated, dotted with piles of council leaflets on tax, public health, crime prevention, and cultural events.

Now the chief executive of the London Collective Investment Vehicle (CIV), Grover likens himself to the proverbial frog in hot water: the heat gradually rose until he realised what was happening. Rather than jumping out of the pot (or surrendering to it), he embraced the challenge. Despite his initial reluctance towards pensions, Grover took charge full time of the project in May this year.

The roots of the CIV began with one scheme that is no longer involved: the London Pensions Fund Authority (LPFA). This organisation does not look after a specific borough’s pensions, but for those who work London-wide—and within the city’s ruling elite.

In 2012, it proposed a full merger with the 33 London borough pensions, citing investment in infrastructure as a key benefit. No one else seemed particularly interested.

“For a number of reasons borough leaders were not keen on the idea of mergers,” Grover explains. “Each borough’s pension fund has a different funding level and maturity profile. There were sufficient differences that meant a merger came with quite a lot of challenges that would be time-consuming and expensive to meet.”

The LPFA, apparently giving up on its city neighbours, turned its sights northwest to collaborate with public pensions in Lancashire.

While this initial plan stalled, the idea of the boroughs working more closely together struck a chord. The remaining 33 began to tackle what at first had looked impossible. Institutional identities, created over the best part of 50 years, hung in the balance—and for what?

In early 2011, New York City’s then-Comptroller John Liu floated a similar plan. The city’s five pension funds together managed $110 billion in assets, and the idea was to actually begin managing them together.

For every new investment identified by internal staff, all five trustee boards had to consent, requiring separate meetings and multiple manager presentations. The lengthy, clunky process hampered New York City’s access to private equity, for example, given its limited fundraising periods.

Despite a year’s research and reporting by staff on how the merged structure would operate—and, more importantly, how much money it would save—unions objected to the changes. Even billionaire Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s public support couldn’t save the proposal.

Local unions

saw the reforms as an assault on their ability to oversee investment decisions

as they stood to lose several seats on the trustee boards. Fresh off the

financial crisis and walking distance from the Street that helped launch it,

union officials balked at bringing in additional private-sector experts to run

the money.

The same scenario played out across the Atlantic. Welsh public pensions tabled a project akin to London’s CIV plan, but shelved it last year amid policy uncertainty. Rather than take up the idea of a merger, the government looked to an independent report outlaying myriad proposals, from shifting to all-passive investments to forced asset pooling.

In 2013, the three counties of Berkshire, Oxfordshire, and Buckinghamshire outlined plans to pool their £5.1 billion, aiming for greater negotiating power, lower fees, and reduced key-man risk. They abandoned these plans this year due to differing opinions about the future.

Karen Shackleton—investment consultant to pension funds for Islington, Camden, and Hounslow—believes the London boroughs’ history of cooperation bodes well for the CIV project.

“I’ve always thought that one of the biggest benefits will be seen during manager selection. The pension fund manager doesn’t need to go through months of procurement processes. All they need to do is go to the CIV—that is a huge advantage.”“It’s probably easier in London because they’ve already been collaborating on things before,” says Shackleton, a senior adviser with AllenbridgeEPIC. “They have treasurers’ meetings every month.”

Local government pensions face other restraints. Staffing levels are far lower than is necessary for most pensions: Most officials overseeing investments are also responsible for administration of benefits, and many are treasurers or financial directors with oversight for multiple areas of local authority budgets.

In addition, central government in the UK is pushing through budget cuts. According to a Local Government Association (LGA) report, in the next two years councils will have to find savings of £10 billion on top of a similar amount over the previous three years—equivalent to a 40% cut in funding since 2011.

But the Brits are nothing if not plucky. Grover has so far managed to get funding for the CIV from 30 of the 33 boroughs, and is confident the final trio—which he declines to name—will also support the venture.

Grover says wider budget constraints “shouldn’t be a problem for the CIV, because costs are relatively small per borough and benefits far outweigh. It’s more of a ‘spend to save’ exercise rather than pure expenditure.”

Lambeth Pension Fund—one of London’s biggest at £1 billion—has an especially active role thanks to Treasury and Pensions Manager Andrien Meyers.

“Being part of the CIV reduces time in procuring fund managers, which is a huge benefit and saves resources,” a council spokesperson says. “The CIV also makes access to certain asset classes like infrastructure easier due to the size of investment that three or four funds could bring as a group rather than as individuals. The major benefit is through the sheer scale of investment as a group, which means reduced fees can be negotiated.”

Furthermore, the project offers “softer benefits”, including knowledge sharing and committee member training.

AllenbridgeEPIC’s Shackleton says a successful CIV will bring major time-saving benefits for the pensions’ few staff members. “I’ve always thought that one of the biggest benefits will be seen during manager selection,” she says. “The pension fund manager doesn’t need to go through months of procurement processes. All they need to do is go to the CIV—that is a huge advantage. These people are hugely overworked, often doing the work of two or three people, and this would allow them to move much more nimbly.”

Some pension committees are “really enthusiastic” about the project, Shackleton adds, while others remain cautious, in no small part because of the money they’ve been asked to dedicate. “It will depend on what managers they have. The CIV will have to demonstrate that there are real cost savings associated with being on the platform.”

Dedicated oversight of the CIV’s funds and managers would also vastly improve governance for London’s pensions, Shackleton explains. “It surprises me that more hasn’t been made of that.”

The timing of the London CIV project could be crucial, and (if successful) have a major impact on the future shape of pension provision in the UK.

In July, Chancellor George Osborne outlined plans to encourage more collaboration between local authority pensions in an effort to cut costs. Remember that £76 million paid in fees in 2013/14?

“The government will work with Local Government Pension Scheme-administering authorities to ensure that they pool investments to significantly reduce costs, while maintaining overall investment performance,” the chancellor wrote.

A consultation is expected by the end of the year setting out what the government expects from the pensions—and specifically what it means by “significantly reduce”.

The policy—contained in just two paragraphs of Osborne’s 123-page summer budget report—also mentions “backstop legislation” for any funds that do not come up with “sufficiently ambitious proposals.” This strongly implies that the government will force collaborations onto any pensions that drag their heels.

Jeff Houston, head of pensions at the LGA, has been involved in preliminary discussions with ministers and pension funds to get a clearer idea of the direction of travel.

“This isn’t about a few funds getting together with £5 billion,” Houston says. Instead, £30 billion is closer to the scale the government wants—although he emphasises that this is not a definitive number.

“I doubt we’ll reach 100% any time soon, unless the government pushes a different agenda, and that’s fine. In principle, others would be able to come in from day one.”If this figure does become a target, London’s CIV project could provide the template. With more than £200 billion in assets in Welsh and English public pensions (the Scots play by their own rules), Houston says the government has indicated a preference for pools of £25 billion to £30 billion. By way of comparison, the biggest individual fund currently is Greater Manchester’s at £13.3 billion.

Houston says the government’s new approach will allow public pensions to establish their own pooled-fund projects before enforcing legislation.

Grover explains that forcing the hand of any investment committee is not how he wants to proceed with the CIV. If it achieves its main objective, he argues, it will be the investment route of choice for its owners, the pension funds, on its own merits.

“We set out six principles for the CIV, and one is that the boroughs are participating voluntarily,” he explains. “I’m not a great advocate of local government pensions being forced to work together. On the other hand, as an ex-civil servant I can see that to drive government policy forward you sometimes need to wield a stick.”

London’s pension authorities shouldn’t need cajoling by central government—they are significantly ahead of the curve.

At the CIV, under Grover’s stewardship, things are progressing at a pace. “The application is in to the Financial Conduct Authority for authorisation, and we’re hoping to get that through by the autumn,” Grover says. “It’s my target to get the first assets under management in by Christmas, but there’s a lot of detail to get through.”

Grover has conducted discussions with “a small number” of fund managers about areas of commonality in mandates, and hopes to get as much as £5 billion to £6 billion on the platform from these negotiations by the end of the “launch phase”.

Next year will see the CIV turn to new asset classes as well as bring more existing mandates under its scope. These are likely to include alternatives and infrastructure, Grover says: “The London boroughs have wanted to be involved in alternative investments before but the cost of entry has often been prohibitive.”

However, the chief executive has a few words of warning for those eyeing the magic £25 billion—coincidentally, both the total assets of London’s pensions and the lower end of that illustrative target mentioned by the LGA’s Houston.

“I doubt we’ll reach 100% any time soon, unless the government pushes a different agenda,” Grover says, “and that’s fine.” But the CIV is being structured to support other public funds from outside the capital. “In principle, others would be able to come in from day one.”

While London Councils’ website highlights policies on builders’ waste and travel passes for pensioners, behind the scenes the London CIV is a potentially game-changing operation for the rest of the 95 UK public funds—and their millions of members.

If London can’t do it, who can? This is a city with grand ambitions—and a history of realising them.

Art by Lauren Tamaki

Art by Lauren Tamaki