For plan sponsors considering embarking on a pension-risk transfer, beware: you’re going to need outside help. A lot of it.

Take WestRock’s recent buyout, for example. On September 8, the Norcross, Georgia-based paper and packaging company announced the transfer of $2.5 billion in pension obligations to insurance giant Prudential.

The reasoning for such a transaction—one of a dozen or so annuity buyouts struck this year in the US—is simple: Responsibility for the livelihoods of 35,000 retirees and their beneficiaries lifted from the plan sponsor’s shoulders and placed safely into the hands of a trusted insurer. WestRock downsizes its pension obligations—and Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation premiums—and participants’ benefit payments are secured.

Actually transferring $2.5 billion worth of pension risk? Not so simple.

The planning and negotiations for this particular buyout—a process that took place over a year and a half—involved enough people to, if not populate a small village, at least crowd a large conference room. Squeezing in alongside Prudential, WestRock, and WestRock’s custodians were Mercer consulting on the deal, State Street acting as independent fiduciary, and Aon Hewitt advising State Street. Add in a handful of legal teams and you have your own pension buyout community.

“There’s a full slate of people who are involved in a process like this,” says Frank Varano, a senior manager at WestRock’s pension. Consultants, actuaries, insurers, lawyers—and, in WestRock’s case, even an outsourced-CIO (OCIO). Having an OCIO involved in the pension-risk transfer was “indispensable,” Varano says. “The asset manager comes in and plays a really important part. They help figure out how we are going to structure the asset portfolio in advance of the deal, how to segregate the assets transferring to the insurer, how to hedge any risk that’s embedded in the deal—really the execution of the transaction.”

For WestRock, Goldman Sachs Asset Management (GSAM) filled that role. GSAM had served as WestRock’s OCIO for several years before the annuity buyout took place—before the company even became WestRock. In 2011, when the firm then known as RockTenn purchased Smurfit-Stone, taking on an additional $1.1 billion in pension liabilities, GSAM was on board to guide the plan toward a de-risking path.

“The Smurfit-Stone acquisition made the pension much more material than it was previously,” says Greg Calnon, managing director at GSAM. “At that time, the focus was on trying to generate returns while also being mindful of risk.”

By mid-2015, RockTenn’s pension was still underfunded by about $1 billion. But the company was on the brink of another major change: a merger with MeadWestvaco, another packaging company whose pension fund happened to be overfunded by $1.5 billion. “We had always envisioned over the long term being on a de-risking path once we were better funded,” Varano reflects. “The merger accelerated our ability to pursue that path.”

The companies merged on July 1; the pension funds on July 2. The newly formed WestRock Company immediately began de-risking the combined plan—and looking toward the possibility of an annuity buyout. “They became a much different type of investor,” Calnon says. “They were now well-overfunded, so the focus shifted to risk management as opposed to generating returns.”

As OCIO, GSAM was in charge of carrying out the de-risking program, swapping out the plan’s riskier growth assets for the high-quality corporate bonds an insurer would be willing to accept in a risk-transfer deal. Meanwhile, WestRock enlisted its actuary and consultant Mercer to investigate how a buyout would play out—what population of plan participants an insurer would take over and how much it would cost to make that trade.

In the fall of 2015, WestRock took the first concrete step toward completing a pension-risk transfer: issuing a request for proposal. Prospective insurers received WestRock’s actuarial data under a non-

disclosure agreement the firm’s legal team drafted, and offered prices based on that data. “We viewed the whole process as a partnership with an insurer,” Varano says. “We tried to be as transparent as we could be in providing data.”

Several rounds of price negotiations later, the decision was made: WestRock would purchase a group annuity contract from Prudential, transferring benefit payment responsibility for 35,000 retirees and their beneficiaries. But the process was far from over. US Department of Labor regulations required that an independent fiduciary evaluate the transaction to ensure the risk transfer was really in the best interest of the plan itself—not just the plan sponsor.

So the village grew. WestRock brought on State Street; State Street brought on Aon Hewitt and some attorneys of its own. Meanwhile, GSAM got down to the business of readying the pension’s portfolio for the asset and liability transfer.

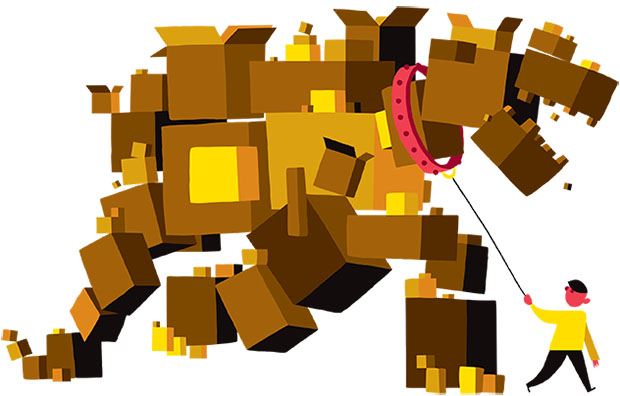

Art by Alex Eben Meyer“The transaction risk management piece is very complex,” says GSAM Managing Director Scott McDermott, “especially for large transactions where they’re spread out over time. There’s a date on which the insurer and plan sponsor formally agree, ̒Okay, we’re going to do this and here’s the price.’ And then there’s the actual closing date. And between those two dates the markets can move.” As OCIO, it was up to GSAM to manage the risk of these market movements and hedge the portfolio as needed. “Ideally we’re making sure that there are no gaps in risk management exposure as this evolves,” McDermott adds.

Art by Alex Eben Meyer“The transaction risk management piece is very complex,” says GSAM Managing Director Scott McDermott, “especially for large transactions where they’re spread out over time. There’s a date on which the insurer and plan sponsor formally agree, ̒Okay, we’re going to do this and here’s the price.’ And then there’s the actual closing date. And between those two dates the markets can move.” As OCIO, it was up to GSAM to manage the risk of these market movements and hedge the portfolio as needed. “Ideally we’re making sure that there are no gaps in risk management exposure as this evolves,” McDermott adds.

There was also the question of determining which assets the insurer would take on. “This was a transaction that included a significant amount of assets in kind,” says Peggy McDonald, a senior vice president and actuary in Prudential’s risk transfer team. “They put a bond portfolio in front of us and we took the assets that we could, which helped reduce WestRock’s premium.” As McDermott explains, “there’s real negotiation that goes on between the plan sponsor and the insurer about what bonds they’re going to take and what bonds the plan is willing to give up.”

By this September, all the parties involved were ready to sign the deal. But the transaction still wasn’t over yet. “You don’t just take out a checkbook and write a check,” McDermott says. “You have all these bonds in the portfolio that need to be delivered. There’s the tedious part of actually confirming the valuations on the securities when everything’s said and done.”

Within two weeks after the September 8 announcement, however, all the loose ends were tied—and WestRock was left with a pension fund “more palatable and appropriate for a company of our size,” Varano says. “The closing went so smoothly, which I think is a testament to the level of rigor put in. The thoroughness of our team, all the advisors that were involved, and of GSAM in particular was paramount to everything going off without a hitch.”

It may have taken a lot of work by a lot of people to secure 35,000 retirees’ pension payments, but for WestRock the end was worth the means. And if the now-$4 billion pension plan ever decides to offload an additional portion of its liabilities—well, the village will get the job done.