David Oxtoby, President, Pomona CollegeThe former chair of Harvard’s oversight board—now president of an elite college—has come to the defense of endowment spending policies after a barrage of criticism that institutions hoard their wealth.

David Oxtoby, President, Pomona CollegeThe former chair of Harvard’s oversight board—now president of an elite college—has come to the defense of endowment spending policies after a barrage of criticism that institutions hoard their wealth.

“These attacks on endowments reveal both an extremely short-term outlook, and a fundamental misunderstanding of what they do and how they work,” Pomona College President David Oxtoby argued today in a commentary published by the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Oxtoby has joined Yale University in pushing back against mounting calls for greater spending on students, ignited last month by a New York Times op-ed titled “Stop Universities From Hoarding Money.”

Both Oxtoby and Yale addressed the op-ed explicitly, saying it “rested on speculation” (Yale) and its ideas “betray a lack of understanding of actions and consequences.”

Mandating an 8% annual spending rate for endowments—as Times contributor and law professor Victor Fleischer proposed—would “hold annual institutional budgets hostage to serious market volatility,” according to Oxtoby. Likewise, Yale said its outflow policy “prudently balances” short-term budget needs with a secure endowment value for the long term.

Yet neither response tackled a major thrust of Fleischer’s criticism. Schools not only ought to pay out more to students, he contended, but they should also spend less on asset management.

“We’ve lost sight of the idea that students, not fund managers, should be the primary beneficiaries of a university’s endowment,” wrote Fleischer, a specialist in private equity and education policy. “The private-equity folks get cash; students take out loans.”

That statement doesn’t ring true for Pomona, according to its latest endowment report. Need-blind admission guarantees full funding of “demonstrated financial need,” while private equity represented less than 10% of its $2 billion endowment as of June 30, 2014.

Oxtoby—perhaps cognizant of the fund’s 55%-plus allocation to alternatives overall—chose not to discuss fees in his response.

His leadership experience also includes the very wealthiest school—chairing Harvard’s board in 2013 as the endowment topped $32 billion—which Fleischer explicitly attacked in his commentary.

Rather than get into fees, Oxtoby argued for flexibility more broadly. Pomona and its peers must retain the ability and independence to preserve capital in strong years, thus cushioning for the weak ones, he said.

“When markets drop, we need, if anything, the flexibility to spend even more to provide aid to students and their families,” he concluded.

Related:Yale Hits Back at Endowment ‘Hoarding’ Accusations & The Endowment Bracket: Harvard, Yale, and the Sweet Sixteen

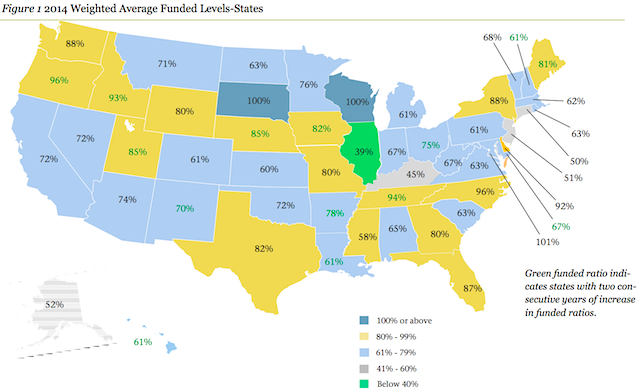

Source: Loop Capital Markets

Source: Loop Capital Markets