Bubbles are extremely rare and attempts to avoid them entail substantial downside for investors, according to research.

Yale School of Management’s William Goetzmann argued in a paper that both investors and the media focus too much on “a few salient crashes in financial history.”

“Bubbles are booms that went bad,” he continued. “Not all booms are bad.”

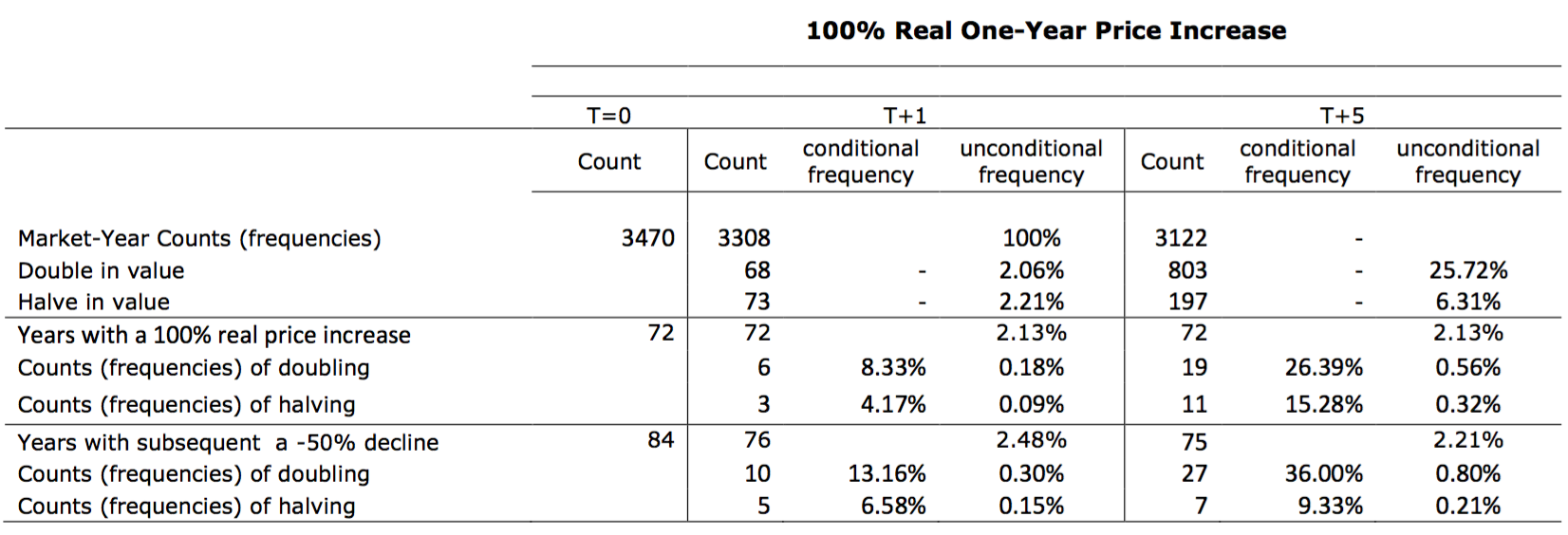

From a study of 21 markets from 1990 through 2014, Goetzmann found only 10% of market booms resulted in a bubble. Market prices were more likely to double again than crash after a 100% gain.

“Bubbles are booms that went bad. Not all booms are bad.”According to the paper, there was only a 4.2% chance of market values halving following a 100% price boom. The probability of values again doubling exceeded 8%.

A longer boom period somewhat increased the probability of a crash, Goetzmann wrote. After three and five-year run-ups, market values fell by half 4.6% and 10.4% of the time, respectively.

“It is important to recognize that the overwhelming proportion of booms that doubled market values in a single calendar year were not followed by a crash that gave back these gains,” Goetzmann wrote. “Most models and analysis of stock market bubbles focus on a few well-known instances.”

Studying these extreme examples outside of broader historical context could be misleading and costly for investors, the finance professor warned. Instead, investors should also get to know the bubbles that did not burst.

“Placing a large weight on avoiding a bubble, or misunderstanding the frequency of a crash following a boom is dangerous for the long-term investor because it forgoes the equity risk premium,” he wrote.

Regulators can also learn from the non-bubbles, Goetzmann wrote, in deciding whether deflating a hot market would truly guard against a financial crisis.

Source: William Goetzmann’s “Bubble Investing: Learning from History”

Source: William Goetzmann’s “Bubble Investing: Learning from History”

Related: Valuations Fail to Deter Private Equity Investors & Pricey Stocks—Not PE Bubble—Causing Record Dry Powder, Rubenstein Says