Past performance may be no guide to future returns, but past volatility can be a guide to future volatility, research has shown.

“Market participants may not want to assume that higher aggressiveness must prove rewarding.”Investors can “sensibly manage” the volatility of their portfolios through reference to a fund’s historic volatility, reported Tim Edwards and Craig Lazzara of S&P Dow Jones’ index investment strategy group, and Luca Ramotti of the ESCP Europe business school.

The researchers analyzed active unleveraged funds in the US and Europe between 2005 and 2015, and found that the percentage of active funds with higher volatility than their benchmarks had increased since 2010 after declining over the previous two years.

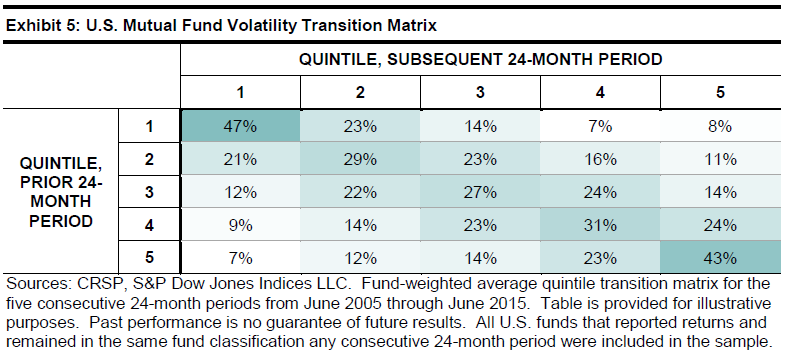

Analysis of volatility over rolling two-year periods showed a high level of consistency among active funds, the researchers said.

“For example, 70% of US-domiciled funds in the least volatile quintile in a given two-year period are in the two lowest volatility quintiles in the subsequent two-year period,” Edwards, Lazzara, and Ramotti wrote. Two thirds—66%—of the most volatile funds stay in the first or second most volatile quintiles, they added.

“Past performance may not predict future returns, but past volatility was a meaningful guide to the future volatility of active funds,” they stated.

On top of the volatility research, the authors also assessed returns in order to determine correlations between risk and return. At the outset of this exercise, the researchers said they expected lower-volatility funds “with persistently higher cash allocations” to underperform US equities, which gained roughly 8% annually.

“In fact, the data would appear to support a conjecture that, within any given fund category, fund volatility is effectively independent of fund return,” Edwards, Lazzara, and Ramotti reported. “The performance of different funds in the same category did not noticeably rise commensurately with their relative risk profile in the sample.”

In other words, while volatility usually remains consistent for active strategies, increasing overall risk levels will not automatically raise returns—nor will lowering risk necessarily decrease returns.

“Market participants may not want to assume that higher aggressiveness must prove rewarding,” the researchers concluded.

Read the full report, “The Volatility of Active Management.”

Related:Time for a New Volatility Model, Says Hermes & Dunatov: Volatility Measure ‘Dangerous’ for Long-Term Investors