When bank prop desks shut down en masse following Dodd-Frank, hedge funds feasted on the suddenly available trading talent.

Now, funds-of-hedge funds (FoFs) find themselves in a protracted version of the prop desks’ situation. And asset owners—who’ve pulled $165 billion from the sector since 2010—are the ones doing the poaching.

“Definitely, there is a lot of talent from funds-of-funds looking for a home,” says Michael Ashmore, a hedge-fund principal with the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS). Ashmore would know. He spent five years at FoFs, and departed for OMERS months before Carlyle shut down his former employer, Diversified Global Asset Management (DGAM).

He belongs to a generation of young(ish) investors raised by hedge funds-of-funds, and succeeding as asset owners.

“The Darwinian, post-financial crisis environment for fund-of-funds investing was so competitive,” Ashmore recalls. “Firms that were considered good—DGAM being one of them, in my mind—had to provide a strong value proposition” to hang on to client assets. “Given that environment, a lot of the juniors that are moving from fund-of-funds to institutional investors these days have serious hands-on experience and technical capabilities.”

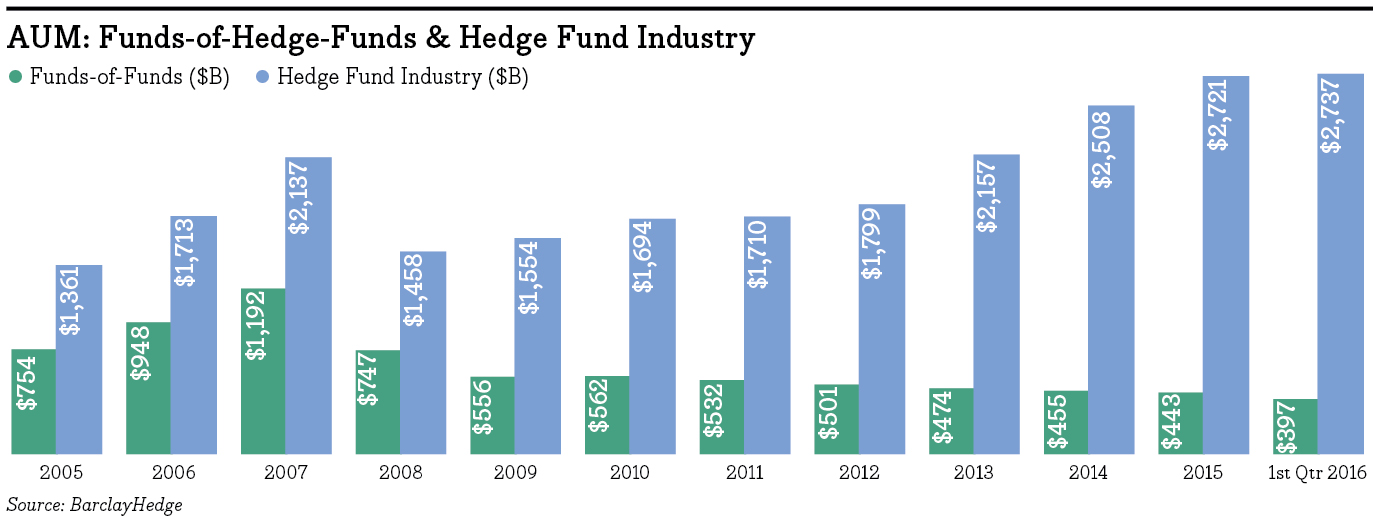

Darwinian environment, indeed. Industry assets have dropped by two-thirds since 2007’s $1.2 trillion peak, BarclaysHedge data show. The number of firms in business shrunk by 36% over the same period, according to Hedge Fund Research.

Hedge funds themselves have enjoyed the opposite trend: An expanding capital base and proliferating firms. Since 2007, assets industry-wide grew from $2.1 trillion to $2.7 trillion. Put another way, funds-of-funds accounted for 57% of hedge funds’ money before the financial crisis. At the end of last quarter, they were responsible for 15%.

ABP, the pension fund for Dutch government workers, manages about as much money as all FoFs in BarclayHedge’s global tracker—$397 billion.

The industry’s downfall came on multiple fronts, according to Sa’ad Shah, a former DGAM managing director and colleague of Ashmore’s. “Firstly, a lot of consultants came into the picture offering the same type of services at much lower fees,” says Shah, who is launching quant fund Qubd Capital this summer. “Second, funds-of-funds are always combating the fee-on-fee problem—particularly when hedge funds overall aren’t doing well. But I think the biggest factor is that investors are becoming more sophisticated. They’re doing their own work.”

Much of that work is being done by industry alumni, and for good reason, insiders say.

“I think all of the skills that I learned transferred to here,” says Martha deLivron, who spent a decade at Permal Asset Management before jumping to the Texas Municipal Retirement System last June. “Obviously, the biggest skill is how to look at managers, and evaluating how the overall portfolio fits together.”

DeLivron is helping to create a $2 billion-plus hedge fund program for the pension, and finds the non-investment skills developed at Permal coming in handy, too. “Sitting down with clients, and explaining how the portfolio works: I didn’t think that would be relevant, but it really is,” she says. “Clients were interested in many of the same things as our board is. And the board is our client at the end of the day.”

Texas Municipal has $1.6 billion invested via FoFs—6.5% of its $24 billion—primarily with Blackstone, the world’s largest hedge fund-of-funds firm. But that $1.6 billion may not be long for the FoF world. It’s a “placeholder” for Texas Municipal while deLivron and her boss deploy $2.4 billion directly. Both used to work at funds-of-funds.

First the assets began to exit, then the talent, and now both in a feedback loop that’s been negative for FoFs, and positive for asset owners (at least on the talent side). Many of the surviving firms specialize in “specific, esoteric strategies,” says Shah—the niches that even sophisticated institutions want to outsource to experts.

Jane Buchan runs one such firm. PAAMCO has survived for 16 years by hunting out and fostering early-stage managers, which tend to outperform mega-funds. In her years as CEO, Buchan has seen asset owners become much more sophisticated. PAAMCO talent has helped.

“We’ve had a lot of people go to institutions,” she says, citing Pasy Wang (senior investments director, California Institute of Technology) and Edgar Smith (managing director, University of Southern California). “Both of them are stars.”

Related: FoFs as Advisors: The Next Iteration? &Carlyle to Close Hedge Fund-of-Funds Arm