At a wedding reception this July, in an Old World palace outside of Krakow, a hedge fund executive described one of his firm’s clients as “a sovereign wealth fund’s sovereign wealth fund.” He didn’t elaborate: The circle of colleagues in black tie knew precisely what makes New Zealand Superannuation Fund the darling of its peers.

That formulation—an x’s x—often bespeaks gender, e.g., hairy-chested men who watch too much sports. But it can do more than simply prop up stereotypes. For example, according to novelist Jhumpa Lahiri, “Everybody writes their first book with a certain innocence, a purity of vision. The writer’s writer writes every book that way.”

From a place quite opposite of the sun-dappled Polish terrace, the young staff of New Zealand’s first sovereign fund approach the US$22 billion portfolio innocent of institutional legacy and with clear-eyed discipline to its vision.

“First, diversification.” CEO Adrian Orr illustrates the fund’s investment beliefs on his whiteboard, channeling the energy and legibility of an abstract expressionist. Luckily, Orr narrates as well. “Next, market mispricing, then asset mispricing, and last comes skill.” To some, “investment beliefs” suggests mere bureaucratic protocol—the sort of document drafted once and never glanced at again. Here in Auckland, they’re treated as dogma, a constitution. That hierarchy of opportunity structures the fund’s every investment decision, its digital interface, and the portfolio itself. Only a handful of active managers have overcome the institutionalized skepticism of skill—the guests of the Polish nuptials among them.

Orr has occupied his glassed-in corner office since 2007, four years into NZ Super’s life as an investor. Like most of his team, the 51-year-old arrived with strong credentials (central bank deputy governor, national bank chief economist), a Kiwi background, and no experience as an asset owner. “The hardest part was interviewing ourselves,” he says, of the early years. “What did we want to be?”

The novel, rigorous investment strategy NZ Super is now renowned for emerged from those conversations. Out went the asset-class model; in came the reference portfolio.

At biannual “RAP”—i.e., Risk Allocation Process—sessions, the investment team defines opportunities for diversification and exploitation of mispriced markets, assets, and—occasionally—skill. Every existing and proposed allocation must prove its mettle against the reference portfolio’s passive exposures and all other investments in the book. Without having witnessed the practice, one imagines the mental gymnastics required to pit timberland against TIPS for inflation protection, and then every other factor. Also, the volume of takeout. No one said being an investor’s investor was easy.

“It has taken two years of crisis and three of building to be very comfortable and consistent with our approach,” Orr says. The fund’s performance—16.8% annual gains over the last five years—bears out the system’s success. A trophy cabinet in the reception area shows that the world has noticed, starting with CIO’s 2012 Innovation Award, displayed front and center. The industry’s most old-guard publication recently reiterated our verdict on its cover—proof positive that NZ Super’s reputation has gone mainstream. If the sovereign fund were a Silicon Valley tech company, it would now be vetting bankers for an initial public offering. And, just like a former startup preparing to go public, this June NZ Super took a major step into the establishment: It appointed a chief investment officer.

I met the affable and broad-shouldered Matt Whineray on a stormy Friday morning in July, a few weeks after he’d been named to the job. Whineray made the morning school run first—his wheels: a Camry sporting baby seats—and then settled in for eggs, coffee, and an interview.

“The hardest part was interviewing ourselves. What did we want to be?”

“I used to fill in on my flatmate’s touch rugby team, and when he moved away, the company offered me his job. I didn’t know what investment banking was”—he had been practicing the law half of his dual degree—“but I wanted to go to New York.” Asked about how he fit into I-banking culture, Whineray laughed. “Lots of the analysts used to have that Hunter S. Thompson quote on their walls: ‘The music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free and good men die like dogs. There’s also a negative side.’ The job was tough, but there was a sense of us all being in it together.”

Investment banking armed the 44-year-old CIO with “very strong transactional capabilities but not portfolio construction experience,” Orr remarked later that day. “So we learned it together.”

Outside the office windows, Auckland’s wintery sky had begun to clear. Orr gathered NZ Super’s leadership team—including newbie Whineray—for a ferry ride to the CEO’s home suburb of Devonport.

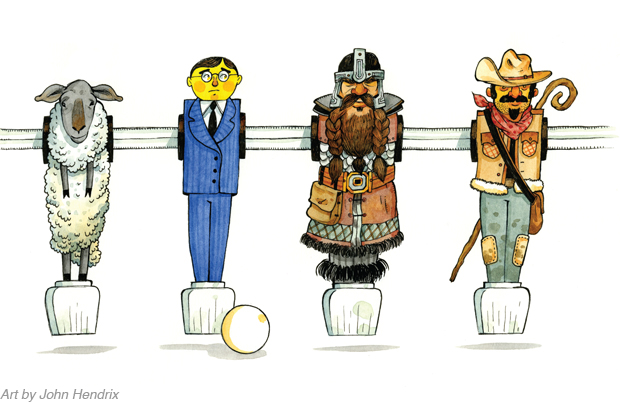

While the division managers held their monthly summit, younger staffers filtered down a floor to the fund’s rec room. Over free beer, darts, and foosball, administrative temps kicked it with senior investors, tech support, and a handful of people who didn’t even work there. Goldman Sachs-style security it wasn’t.

The scene suggested that NZ Super won’t turn into just another sovereign wealth fund anytime soon. Taped to the wall, a fund-wide foosball bracket matched up Adrian “Puff Daddy” Orr with Julius “Loves Rugby” Ghyoot, an IT server consultant. The winner would go on to face operations analyst Michael “Man, OH YEAH!!!” Duff.

Whineray’s talents on the rugby pitch may have earned his entrée into finance, but his foosball skills take no credit in the latest promotion. According to the posted bracket, Tim “The Dog” Koller, a portfolio manager, knocked out his CIO in the first round. One imagines Whineray took the loss gracefully. As the fund’s head of communications says, “Kiwis don’t tend to have big egos. Anybody here who got too up on themselves would have the mickey taken out pretty quickly.” It may not be written into the investment beliefs, but surely that counts as purity of vision.