“We are taking control of our own destiny.”

It may sound like a rallying cry from the protagonist of a Hollywood epic, but for Mark Redman this encapsulates his approach to private equity investment.

The London-based head of Europe for the private equity arm of Canada’s Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS) has, in the past few years, overseen an unusual move by the C$65.1 billion (US$59.7 billion) pension to bring a significant amount of its allocation under in-house management. In five years, OMERS has reduced its reliance on third-party managers significantly—now just 30% of its allocation to private equity is outsourced. It has carried out five deals in that time, with a combined value of US$1.3 billion.

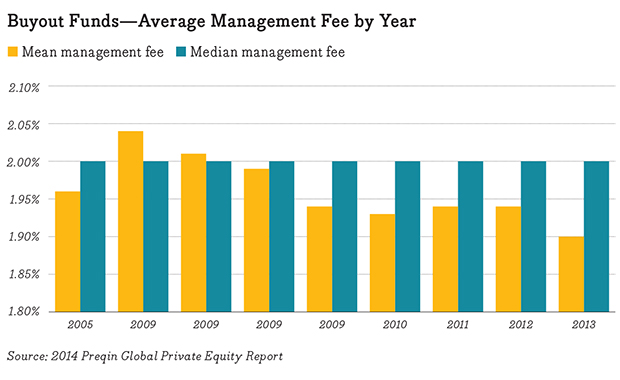

Redman explains the main benefits of the move: “How we track our returns is simpler and our performance is materially better. We have better asset selection, but we are not made to pay the fees.” He argues that pension funds can pay away “large amounts of returns in fees and carry” through using external private equity managers. Indeed, in a world where the active management of listed equity funds is (in general) getting cheaper, the traditional private equity fee structure of a 2% annual management charge with a 20% performance fee is starting to look pricey—and, as the chart below shows, there has been little downward movement on these fees in the past nine years.

UK pension manager Railpen (RPMI) is also eyeing a move to investing directly in private equity deals. Richard Moon, a specialist private equity and infrastructure investment manager at the UK group, says RPMI is seeking to cut costs by “consideration of a number of investment models outside the traditional fund model, such as co-investing or going direct with private equity and infrastructure”.

“If you’re able to add the right staff, there is a point where costs become a major driver,” asserts Massimiliano Saccone, founder of Milan-based advisory XTAL Strategies. He argues that the fixed costs of running an in-house team are likely to be lower on an ongoing basis than paying annual management charges to external managers. “If you have enough money to do your own stuff, you can get operational leverage and save money,” he adds. “This also produces alpha—the compounding effect of saving is a big amount of money.”

Pension fund giants such as the California Public Employees’ Retirement System and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board have also chosen to go direct with some of their private equity holdings in much the same way as a growing number of funds are doing with infrastructure allocations.

So why aren’t more investors doing this? The reasoning seems straightforward: If you have a significant allocation to private equity but don’t want to pay 2 and 20 every year for the privilege, why not just do it yourself?

Redman refers to European peers being “nervously critical” of OMERS’ move—and those peers might just have a point.

Theodore Economou, CEO and CIO of the CHF3.8 billion (US$4.2 billion) CERN Pension Fund, believes any investor wishing to take the direct route must start with a substantial amount to allocate—and not just to the investments themselves but to the establishment of a highly skilled team. Economou argues that, for this reason, the direct route is—and will likely remain—the preserve of the very largest funds in the world.

Typically, he says, bringing private equity investment under your own roof requires “a very large team”—in excess of 20 people—and the finances to travel the world, deal on the secondaries market, facilitate co-investments, and even sit on company boards. He adds that “if pension funds substitute themselves as the general partner then the difficulties are much greater” than a traditional fund, or funds-of-funds, approach. “In a number of jurisdictions, the fiduciary liability risk associated with such an approach is not insignificant,” he says.

Keeping those staff will cost you, too, says RPMI’s Moon: “If you’re buying direct stakes in private companies, then you have to compete in a different employment pool to the one that traditional pension funds typically fish in for talent. If you look at the amount of money private equity funds make through revenues, you’ll see that even moderately sized private market GPs with multiple funds are making hundreds of millions of pounds. That’s the pool of capital they can use to compete for talent.”

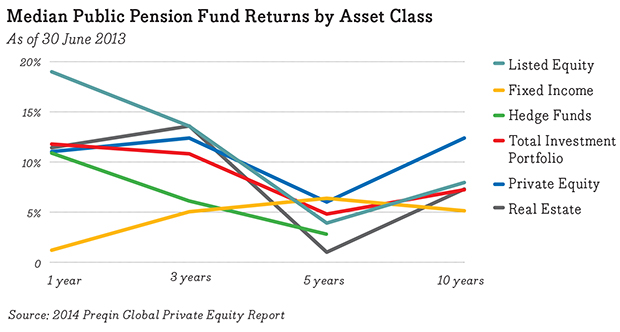

Indeed, according to a recent report by private equity research specialist Preqin, the biggest allocators to private equity are those that have the deepest pockets—and even then they are ploughing substantial portions of their overall portfolios into the asset class. This is not an area for merely dabbling.

“If you think an opportunity in a particular strategy is secular and is likely to remain attractive for a long time, then it is probably worth it—but if the time frame for the opportunity is constrained, then you should probably consider other investment models for access,” Moon says.

While there is unlikely to be a massive industry exodus from traditional private equity funds, providers are starting to feel the glare of investor scrutiny more and more, according to Sanjay Mistry, principal at Mercer. He says that his company has noticed an uptick in demand for more “tailored” private equity mandates as schemes seek to obtain more control over their assets.

“Many clients have taken the view that the traditional fund-of-funds model has been challenged,” he says. “The market has been responding by lowering fees and providing bespoke options.”

One such halfway measure between buying funds and ditching them altogether is outsourcing elements of the private equity function—namely, the trickiest part: sourcing the deals.

Economou argues that this is a more attractive option than establishing a full in-house team: A CIO can hire analysts to keep control of portfolio construction and execution, while employing a consultant to do the legwork—sourcing deals, performing due diligence, and supporting portfolio construction.

It is tempting to pen the “evolution, not revolution” cliché when observing this trend towards greater flexibility in private equity allocations, but Chief Investment Officer prefers to avoid clichés like the plague. OMERS’ Redman has no such qualms, however, and concludes his case for in-sourcing with another Hollywood-esque quip: “We are at the vanguard of a revolution, at the beginning of a new trend, but it is happening slowly.”

While this may not be uttered by Russell Crowe anytime soon, it certainly has the ring of truth about it.

—Nick Reeve