“A pension fund is really not about a single portfolio. It is about the total portfolio. You have to take into account the total impact of an action, not just the single impact.”

So speaks SPK CEO Peter Hansson who, along with CIO Stefan Ros, has just completed the most dramatic asset allocation overhaul in the €2.6 billion pension fund’s history. It is this holistic thinking that permeated the entire two-year process, and—they hope—will secure the future of the pension fund run for half of Sweden’s banking system.

Hansson and Ros sit opposite me in the main meeting room of SPK’s office in Stockholm—a floor of the impressive Westmanska Palace—looking remarkably relaxed. Holiday season has just started in Sweden, but the end of this process is just as likely to be keeping spirits high.

“It’s been a fantastic trip and interesting for us as financially-interested and educated people to build a portfolio from scratch,” says Hansson.

As he begins to explain the process behind their new

allocation, Ros illustrates the journey with diagrams on the room’s whiteboard.

(No Swedish meeting room is complete without a whiteboard—and it is always

used.)

“It’s been a fantastic trip and interesting for us as financially-interested and educated people to build a portfolio from scratch.”—Peter Hansson, SPK CEO.

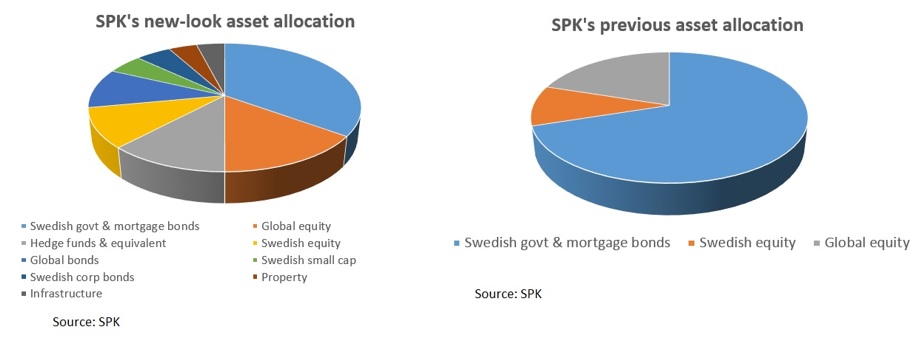

Gone is the traditional 70-30 split that favoured Swedish government bonds and mortgage-backed securities. In fact, half of that 70% exposure to government bonds has been sold entirely, in favour of a new, flexible global bond mandate, property and infrastructure allocations, and an innovative “alternative risk premia” mandate (more on that later).

Why Now?

SPK is a stable, established pension which has been operational since 1944. It has never been in deficit—Sweden’s strict solvency rules would not tolerate it—and has an especially strong funding ratio. So why change a successful model?

The trigger for this overhaul came from an unexpectedly helpful rule change by the Swedish financial regulator. In 2012 the regulator altered the discount curve used by the country’s defined benefit pensions to calculate their liabilities. It introduced an “anchor” at the longest end of the curve—and, in the case of SPK, halved its volatility overnight.

At the same time, Hansson and Ros were discussing their holdings in government bonds. Yields had been declining for several years, ensuring that SPK’s liabilities were matched. But this was not going to last: As with most of the stronger European governments, Sweden’s debt was reaching record low yields, which were bound to unwind at some point.

With the additional risk budget granted by the regulator’s change, SPK set about discussing with its “inner ring” of selected partners—including Danske Bank, Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, and Nordea—options for a modernised asset allocation.

“We discussed a couple of hundred portfolios and slimmed it down to three options—this took about a year,” Hansson explains. “After a year we had a set idea of the asset allocation and at the beginning of this year we started to look for managers.”

Most of the managers chosen are fairly close to home: Handelsbanken has been given two new mandates in Swedish corporate bonds and Swedish small cap, while Swedbank has retained its place managing Swedish government bonds, albeit a smaller and more flexible mandate.

Other Nordic groups, including Danske, Carnegie, and Brunner, have also been added to the mix, alongside a eurozone property allocation run by UK-based Aberdeen Asset Management (with another as yet unnamed Nordic group managing local real estate assets), and global bonds run by Goldman Sachs Asset Management.

Infrastructure is another new addition to the fund. Although the manager will not be named until the final legal documents have been signed, Ros says the mandate is focused on “global core” assets with low yields and low risk.

Finally—and as Hansson and Ros suggest, most interestingly—SPK has introduced a 12% allocation to hedge fund strategies, most of which is given over to “alternative risk premia”. Once again the manager is yet to be named, but the SPK duo are nevertheless excited to give as much detail as they can about this new direction for them.

Continues on next page…

Ros describes the strategy as a “systematic” process for targeting specific areas of risk and return not already represented in the rest of SPK’s portfolio, all with a “significantly lower cost” than most traditional hedge funds. The manager is to be given access to details of the rest of the pension’s portfolio and effectively tasked with plugging the gaps between the various asset classes.

“It’s done in a hedge fund way but with daily liquidity—it’s something quite new for us,” Hansson adds.

In-House Outsourcing “This way we don’t need to go round and hug individual properties—there are no sentiment issues.”—Stefan Ros, SPK CIO, on outsourcing real estate.

The entire process of designing and allocating the new positions was monitored and controlled in-house. Hansson dismisses the idea of using consultants: “We should be the ones who understand fully the nuts and bolts.”

But when asked whether SPK considered following a number of its European counterparts and investing directly in real estate or infrastructure, Ros and Hansson are adamant this is not the way they do things.

“One of the areas we think we’re good at is hiring and firing managers,” Hansson says. “No manager is best at all times. If we had a huge amount of internal managers we could have a staffing or employment issue if we wanted to change anything.

“We used to have real assets managed in-house 10-15 years ago, but we sold these because of the inefficiencies. An 8% allocation to real assets is sizeable but it is more efficient to outsource.”

Stefan Ros puts it more succinctly: “This way we don’t need to go round and hug individual properties—there are no sentiment issues.”

2015 and Beyond

Now that the new asset allocation is in place, SPK’s concern can turn to the ongoing management of performance and solvency. Hansson explains that they have a shortlist of two or three alternative manager options for each asset class that are continuously monitored to ensure SPK has the right ones in its first team.

The pension also has its own innovative risk monitoring tool, R-MAP (Risk Management Action Plan), designed to ensure SPK does not run the risk of being even close to underfunded—something that Hansson points out would reflect particularly badly on the banks that contribute to the scheme’s funding.

This robust framework is designed to keep SPK in surplus for the foreseeable future. As more Swedish pensions assess what rising rates and regulatory changes mean for their asset allocation decisions, SPK has shown what is possible.

And if you needed any more convincing that Hansson knows what he’s doing, look no further than his nomination for Chief Investment Officer’s 2014 European Innovation Awards, and his position in our Power 100—two years running.