Longevity may not always be the big risk to your portfolio it is now. In the summer of 2009, David Dorr, then-CEO of life settlements trading platform Life-Exchange Inc., claimed: “We are at the apex of the longevity growth curve.” Writing for the Journal of Structured Finance, he made the case that life expectancy is set to fall in the decades ahead.

The strain that a growing world population will place on resources, unsustainably high health care costs, poorer quality food, and falling living standards were all cited as factors that could increase mortality and even cause life expectancy to “drop quite dramatically.”

It is important to mention that Dorr went on to talk of arbitrage opportunities for investors in his asset class—which essentially bets on people dying earlier than expected—but his paper nevertheless raises an interesting issue: What if people stop living longer?

There is already evidence that life expectancy is not increasing at the rate it once was.

First, the numbers: According to the World Bank, a Japanese person born in 2012 could expect to live 15 years longer than a compatriot born in 1960—an improvement of 3.6 months for every year. But much of this improvement came in the 1960s and 1970s: Between 1987 and 2012, Japanese life expectancy from birth improved by 2.3 months per year, half the rate of the previous 26 years and behind Germany, Australia, and the UK. In the first 12 years of the 21st century even the average life expectancy in the US improved by more than Japan.

In the UK, there is similar evidence of improvements slowing. The Department for Work and Pensions reported last year that between 1973 and 2013, male life expectancy at age 65 improved by two months per year, from 13.1 years to 21.8 years. Between 2013 and 2058, the rate of improvement is forecast to halve.

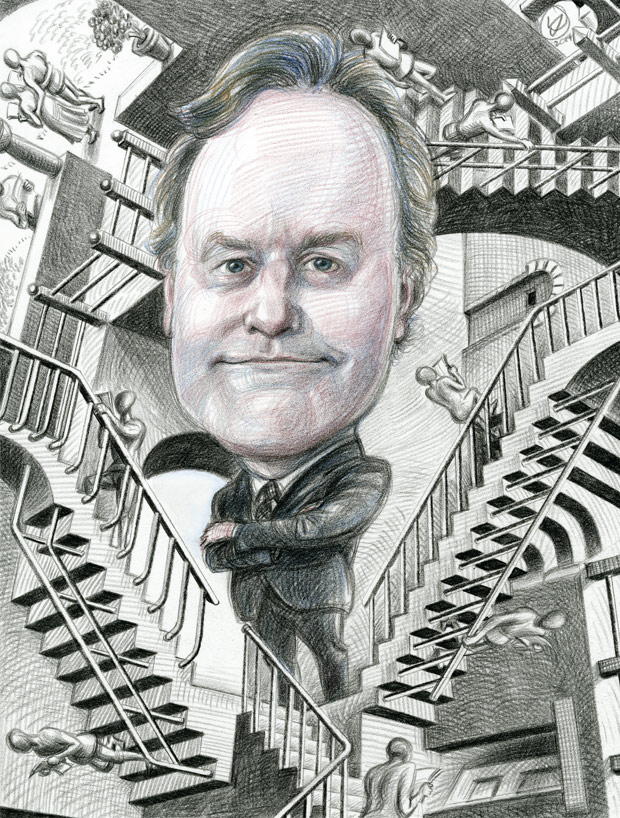

America’s mortality improvement rate is also declining, according to data from the Society of Actuaries. Although this figure is different to longevity, it backs up work by renowned scientist Jay Olshansky. A professor at the University of Illinois and specialist in life expectancy and health, Olshansky has co-authored several research papers and articles arguing that the human body is not built to last.

In a 2005 co-authored report published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Olshansky and other academics argued that obesity trends in the US “threaten to diminish the health and life expectancy of current and future generations.”

“Unless effective population-level interventions to reduce obesity are developed, the steady rise in life expectancy observed in the modern era may soon come to an end, and the youth of today may, on average, live less healthy and possibly even shorter lives than their parents,” the report stated. “In fact, if the negative effect of obesity on life expectancy continues to worsen, and current trends in prevalence suggest it will, then gains in health and longevity that have taken decades to achieve may be quickly reversed.”

(CIO tip: Don’t sit next to Olshansky at dinner parties.)

So, does this mean longevity risk is dying?

David Blake, professor of pension economics at London’s Cass Business School, says it could be—but warns investors not to dump those hedging plans just yet.

“There is an upper limit to the human life span, and that appears to be around 115 years,” Blake says. He adds that “more and more people are approaching that upper limit” as each generation ages.

“That suggests an increasing number of people will survive to higher ages and will be dying in the range of 100 to 115. If that’s going to happen, there is still a long time until longevity isn’t a risk. Pension funds in the next 20 to 30 years definitely have got to work with longevity.”

Medical advances such as nanotechnology and gene therapy could also push up the number of centenarians as society as a whole ages—although, as Olshansky has argued, it would require an unprecedented rollout across the world’s population to make a meaningful impact on life expectancy.

Blake is also cautious on these advances, but for a different reason. “The real risk to society is that life expectancy increases at a greater rate than healthy life expectancy—that is what is going to challenge social welfare budgets,” he says.

A quick estimate indicates that, to reach 115, a 65-year-old retiring today on the average US pension of $29,000 a year would place a $1.45 million liability on his or her pension fund, without factoring in inflation.

“The big takeaway is that we all need to be saving like hell,” Blake concludes.

There is another school of thought on longevity—and defined benefit pension CIOs should probably look away now.

In his trademark baggy jumper, paired with a ponytail and a long brown beard stretching comfortably over his chest, super-centenarian advocate Aubrey de Grey looks decidedly more like an advocate of New Age than old age. But he has a radical set of theories that would send shivers down the spines of most actuaries.

Described by Blake as a “wild card,” critics accuse the controversial author and theoretician of hunting publicity as much as he hunts for a “cure” to aging and degeneration. Most famously, nearly 10 years ago, de Grey voiced his belief that the first human to live to 1,000 is already drawing a pension.

Another CIO tip: Don’t sit de Grey next to your scheme actuary at dinner parties. What’s the average total pension for one 65-year-old retiring today if he or she reaches 1,000? $27 million.