Throw the term ‘smart beta’ into a room of asset owners, managers, consultants, or even financial journalists and you’ll hear at least one person groan, “Not this again.”

It’s been called snake oil, a tired buzzword, a marketing ploy… the latest repackaged investment strategies—this time for factor investing.

That said, the groans haven’t stopped investors from diving head first into smart beta. The controversial label is gaining a great deal of assets—and fast.

Unfortunately, the discussion around smart beta has mostly centered on loving or hating the name—even though no one seems to agree on what ‘smart beta’ actually means. Is it in fact smarter than other beta? Is it even beta?

But look beyond the endless debates about the nomenclature and the proliferation of substitute labels. Do digital traffic patterns point to clear winners and losers—and who are they? Does it pay off to distance from smart beta?

Too Many Names, Too Many

Problems

On a fateful day in London in 2000, Towers Watson coined the controversial expression “smart beta.” Since then, the number of providers and implementers has soared, flooding the space with products and almost as many names for this burgeoning category.

Investors’ appetite has also picked up in the last few years. According to Morningstar, assets in smart beta funds (or whatever providers choose to call them) exceeded half a trillion dollars in 2015, up from just $200 billion in 2011.

In February 2015, Towers Watson announced its global institutional clientele allocated more than $8 billion to smart beta in 2014, bringing their total exposure to about $40 billion—double the figure of two years prior.

“It is no surprise to us that smart beta strategies are being implemented at this rate, given their inherent relevance for most institutional investors,” Craig Baker, Towers Watson’s global head of investment research, said last year.

But Baker was quick to add that with more money comes more problems.

“While it is satisfying that our clients have been able to benefit first from a range of smart beta strategies, we are somewhat concerned about the proliferation of products now on the market that claim to be smart beta, particularly in the equity area,” he said.

And the range is wide. Though some firms have stuck with smart beta, many more have veered away from the controversial label and gotten creative.

Of the biggest players in the space, Research Affiliates, Russell Investments, and Towers Watson remained traditional. Others—including Northern Trust, State Street Global Advisors, TOBAM, and BlackRock—chose names like advanced or strategic beta, engineered equity, or maximum diversification and anti-benchmark strategies.

But using non-smart beta labels may have disadvantaged firms in establishing a strong brand—at least online.‘’

According to Google Trends data, web searches for ‘smart beta’ really found momentum in July 2013, despite the term’s roots in the early 2000s. Interest remained modest until a sharp spike in May 2014, followed by a slowdown in August. Data show smart beta searches have continued rising since then, maintaining levels well above 2013’s.

In comparison, Google’s data on strategic beta, advanced beta, alternative beta, and engineered equity are nil: Not one of the smart beta substitutes produced any meaningful search traffic from January 2013 to July 2015.

Another set of data shows queries for smart beta triumphed over related phrases. Fundamental index and factor investing received some hits online in the 2013 to 2015 period, but were marginal compared to smart beta. Equal weighting registered no interest.

Direct comparisons of firms, their smart beta products, and their respective names are inconclusive using Google Trends data. Most of the big players in smart beta are also financial giants whose broader search data obscures smart beta-specific traffic.

Looking Beyond the Smart Beta Noise

“You have to remember, institutional investors aren’t going to be Googling ‘smart beta’ to choose their managers or products,” Matt Peron, Northern Trust’s managing director of global equity, argues. “Our ‘engineered equity’ strategy is geared towards institutional clients so we focus on delivering deep and high quality research rather than online marketing.”

Even Research Affiliates—a godfather of smart beta—says establishing an online presence has been important, but only in broadening the awareness of smart beta.

“Our presence on the internet has roughly tripled in the last two years to include tweets, Facebook acknowledgements, and hits on our website,” Rob Arnott, the firm’s founder and CEO, says. “These have directly helped our branding and public awareness. But in terms of direct impact on sales and adoption of our strategies? Only tangential.”

And State Street Global Advisors’ 2014 smart beta survey confirms these claims.

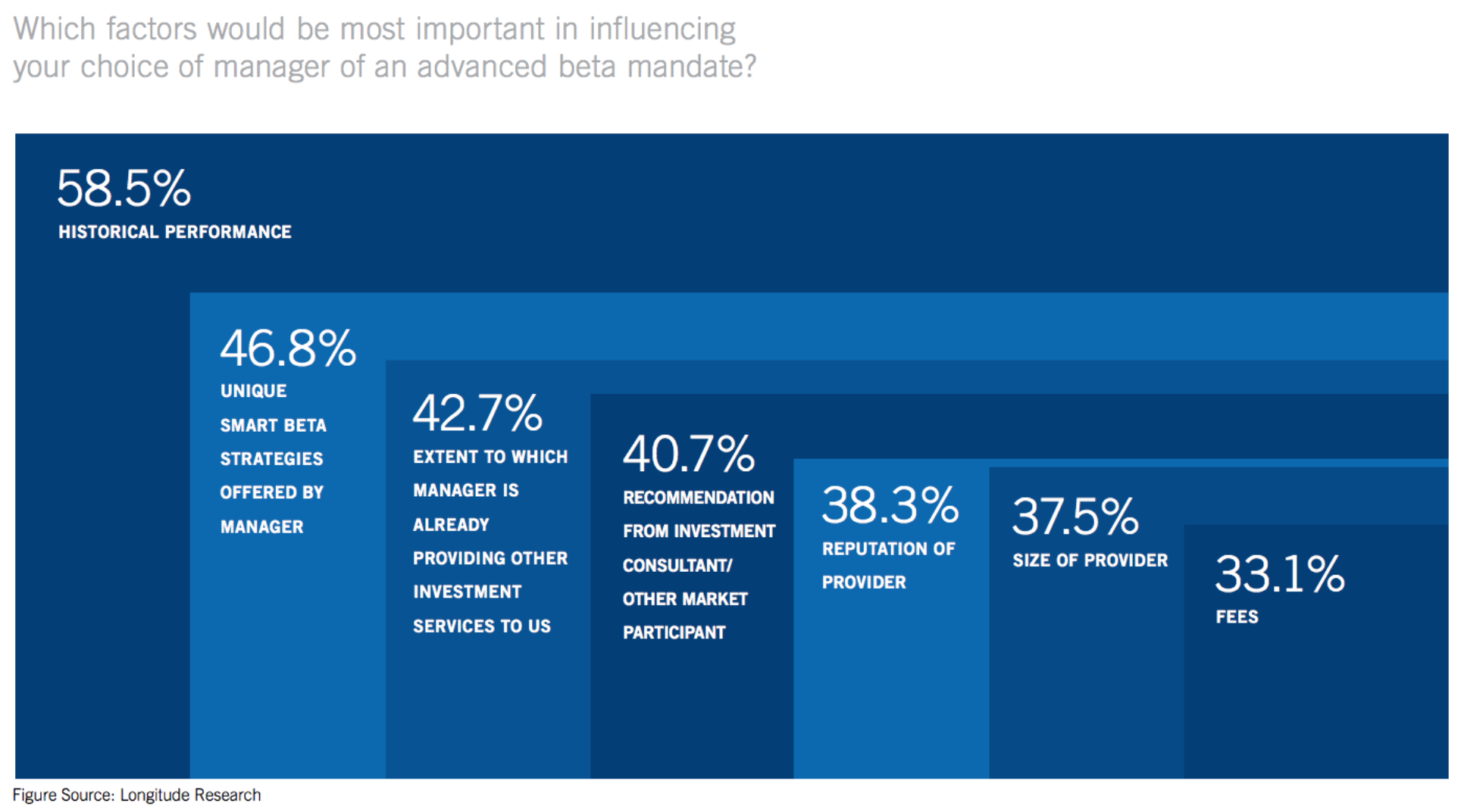

Source: State Street Global AdvisorsInvestors identified historical performance as the number

one factor (58.5%) in choosing a manager for a smart beta mandate, followed by

the firm’s ability to offer a unique strategy (46.8%). Others included an

existing relationship with a provider, recommendations from consultants, the

reputation and size of the manager, and fees.

Source: State Street Global AdvisorsInvestors identified historical performance as the number

one factor (58.5%) in choosing a manager for a smart beta mandate, followed by

the firm’s ability to offer a unique strategy (46.8%). Others included an

existing relationship with a provider, recommendations from consultants, the

reputation and size of the manager, and fees.

Online presence or product names were not mentioned.

Northern Trust believes it has shaped its smart beta approach to target asset owners’ desire for a unique take on the strategy.

The Chicago-based firm chose ‘engineered equity’ about four years ago and Peron says differentiating the strategy from smart beta has been “a little bit” beneficial in the short term, though he adds the firm is confident it will pay off in the long term.

According to the firm’s white papers, the approach involves deliberately moving an equity portfolio out of uncompensated risks and adding in intentional and compensated risks, indicating a more active strategy than the traditional smart beta.

“When smart beta became more prevalent, we felt the name didn’t quite capture what we were trying to do,” Peron says. “Clients say they appreciate that we’ve chosen a specific name that resonates with our factor efficiency work. And the criticisms about smart beta gave us more the reason to use ‘engineered equity’. We’re bypassing the smart beta noise.”

However, this “smart beta noise” extends beyond the variations in nomenclature, according to Research Affiliates’ Arnott. He and his firm introduced the fundamental index in 2004, spawning many mimics and gathering $150 billion in assets over the last 11 years.

“Smart beta is a convenient catchphrase that captures interesting strategies,” he says. “But it becomes a problem when everyone gets into smart beta and then stretches the definition to include non-smart beta strategies.”

He adds that all smart beta strategies should seek to sever the link between the price of a stock and its weight in the portfolio while maintaining most of the advantages of cap-weighted indexing such as low turnover, strong liquidity, transparency, and the ability to backtest.

And unless the sector’s many players can deliver everything included in that definition—despite their linguistic creativity—he believes they will slowly fade out.

Adapt or die, Arnott says. “Even if some are used heavily enough to have staying power, all of these ‘smart beta’ strategies will either migrate towards a well-established definition or cease to mean anything.”