In 2005, an article appeared on the BBC’s international news website titled “So What Are Hedge Funds?”

It had been penned by then-Watson Wyatt consultant Robert Brown and laid out the very basics of who, what, and why. The article explained how these investment houses, which were unlikely to be found on any high street, shrouded their strategies in so much mystery only their clients knew what they were doing—and how well.

During the rest of 2005, according to Google Trends’ search archives, the hedge fund sector gained scant further coverage in a news agenda dominated by Hurricane Katrina, George W Bush’s second term in office, and the death of Pope John Paul II. But hedge funds were on their way. For a group that had lived in the shadows of the Wall Street titans, its time was now. In 2005, some 2,073 of these vehicles launched, according to Hedge Fund Research (HFR). This was just a few hundred fewer than the total launched in the two preceding years combined. An average of half that number have launched annually since.

The following year, hedge funds began creeping onto financial press agendas. Interest in the sector had been piqued and people wanted to know more. In 2006, the term “hedge fund returns” made its debut on the Google Trends register. Whether it was investors, bored with the equity bull market or investment bankers bored with their day jobs, 2006 marked the start of a relationship with hedge funds that, on the surface at least, reads like any long-term love affair.

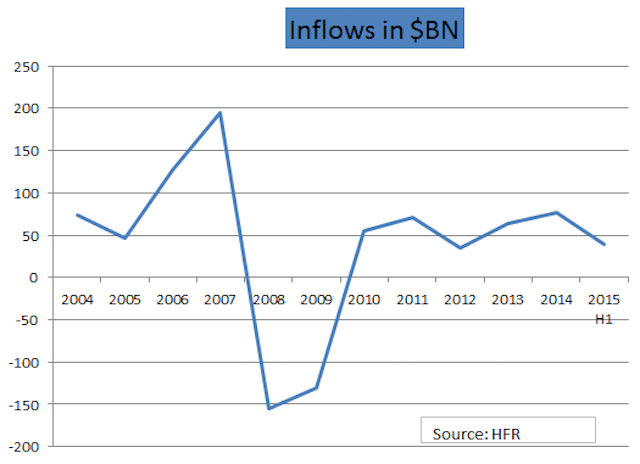

As interest grew, inflows swiftly followed.

In 2006, a net inflow of $127 billion moved into the sector; in 2007 a further net $195 billion came in, HFR data show. Combined with investment returns, industry assets rose to record levels. HFR estimated industry assets in 2006 to have hit $1.46 trillion—from $1.1 trillion in 2005—and reached $1.84 trillion in 2007.

But, as with all relationships, there are ups and downs. Even though most could not have predicted the scale of what followed, 2007 was already displaying signs of investor insecurity. BNP Paribas announced it was suspending some money market funds as it couldn’t value them on a regular basis. UK bank and mortgage lender Northern Rock had to be bailed out by the government and others began to look shaky. Phrases like “credit crunch” and “mortgage-backed securities” entered journalists’ style guides.

If the financial world in general was realizing liquidity doesn’t just happen by accident, many were interested to find out how these newly arrived hedge funds were dealing with the sudden drying up of markets.

In 2007, Google searches for “hedge fund loss” peaked for the third time. These searches nearly overtook those looking on the more positive “hedge fund returns” side of the equation—and maybe with good reason. As people were wondering about losses, hedge funds were coming through with the goods.

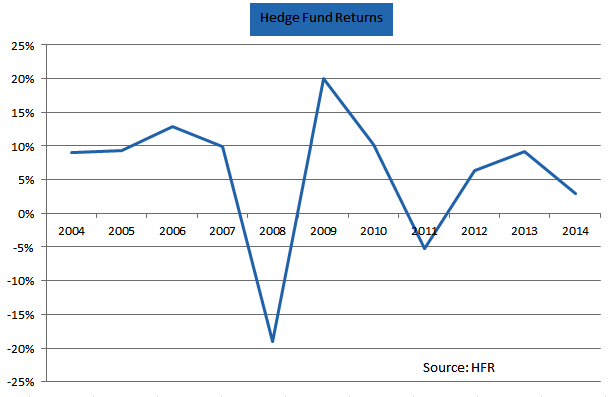

Returns fell through the floor as 2007 drew to a close, with the average fund losing 20%. At the same time, global equity markets were losing up to double that but Google Trends suggest many were not convinced by the argument that they had outperformed the market. It is noteworthy that the term “absolute return” saw a good deal of search activity over this period.

As might be expected in any relationship under stress, one side began asking some pointed questions about the other’s activities. Soon after the 2007 peak of people searching about losses, “hedge fund fees” began to loom large in Google Trends data.

With losses, fees, and a financial whirlwind that very few predicted or prepared for, it is no coincidence that passive investment began to attract investors’ eyes. Data from ETFGI show a definite shift in inflows to ETFs and other index-linked products with assets under management taking a bite out of the lead hedge funds had built up over the past decade.

.png)

As 2008 came to a close and equity markets approached their lowest ebb for more than a decade, investors—and let’s be honest, journalists—wanted to know how much hedge fund clients were paying to see their money washed down the financial drain. Searches for losses and fees peaked simultaneously.

Investors must not have been happy with what they found as net inflows collapsed into net outflows. In 2008 and 2009, combined net outflows of $285.6 billion undid much of the $321 billion that had been allocated to hedge funds all over the previous two years.

These outflows were also a reflection of the huge reduction in hedge fund quantity. In 2008, nearly 1,500 hedge funds called it a day and closed—or were made to do so. In 2009, 1,023 did the same, according to HFR.

They say that when trust is gone in a relationship—and charging clients lots of money to lose their assets will make that happen—it is very difficult to get it back. Over the next year or so, searches for hedge fund fees roughly equaled those for managers’ remuneration. If investors were hurting, they wanted to know how the other side was feeling, too.

A March 2010 New York Times article announcing “Pay of Hedge Fund Managers Roared Back Last Year” was one of the many detailing the billion-dollar paychecks earned in 2009 by the top 25 managers. President Obama suggested some 18 months later that the sector was not paying enough tax.

However, it’s said that a storm clears the air, and that seems to be the case with hedge funds and their clients. Rather than abandoning the industry and its abundance of yachts, investors started pushing back. The largest allocators began demanding lower fees, better terms, and greater transparency. Custodians and asset servicers gained new hedge fund clients who were willing to make it up to them.

Managers reported their risk control techniques, stopped promising the moon and stars, and opened up about what they were doing. In short, hedge funds became better partners.

For their part, investors asked more questions, adjusted their expectations, and did not demand hedge funds shoot the lights out to make up for failings elsewhere in institutions’ portfolios.

“They say that when trust is gone in a relationship—and charging lots of money to lose investor assets will make that happen—it is very difficult to get it back.”Ever since, assets under management have risen as net outflows have turned to net inflows, but at a slower and steadier rate. Returns have leveled out from the dramatic positive and negative double digits.

And how does this all play out on Google Trends?

Searches for loss figures had all but disappeared except for brief occasional spikes—most recently at the start of 2015—while interest in returns has steadily reduced. This might mean investors are less keen to know how much they make and realize there is a broader function for hedge funds in a portfolio. However, searches for fees and compensation now rival those for returns. This could mean investors are keeping an eye on the wider market—once bitten, twice shy.

For all the noise that might sway these trends, the result of the past decade has been to create a more balanced LP-GP relationship. Hedge funds have gone mainstream.

Some large investors have made recently made waves by disputing fees, returns, hedge funds’ function in a portfolio, and kicked them out of the house.

But not all relationships work out, anyway.